|

Return To Main Page

Contact Us

How to Sell

‘Carbon Neutral’ Fossil Fuel That Doesn’t Exist

Energy companies are

starting to pitch the idea that planet-warming natural gas can be

erased by paying villagers to protect forests. Experts can’t make

the math work.

Volunteers clear

vegetation that would otherwise stoke wildfires in forests around

their village near Mbire, Zimbabwe. Their work is funded, in part,

by the sale of fossil fuel thousands of miles away.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

By Stephen Stapczynski,Akshat R athi, and Godfrey Marawanyika

August 10, 2021, 9:01 PM PDT

The junior traders at

TotalEnergies SE were essentially winging it last September by

orchestrating the French energy giant’s first shipment of

“carbon-neutral” natural gas. It’s the greenest-possible designation

for fossil fuel and an important step in making the company’s core

product more palatable in a warming world. Nailing down the deal

involved googling and guesswork.

Listen to this story.

Total had proposed the trade after learning a client had already

purchased two carbon-neutral cargos from rivals at Royal Dutch Shell

Plc, according to people with knowledge of the deal who asked not to

be named discussing a private transaction. One of these insiders

said that only after getting the go-ahead did the inexperienced team

attempt to figure out how to neutralize the emissions contained in a

hulking tanker full of liquified natural gas. Their first step was

to search the internet for worthy environmental projects that might

offset the pollution.

‘This whole bush can be

razed to the ground if we don’t do what we’re doing,’ says Kembo

Magonyo, one of the volunteers.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

Thousands of miles away, a Zimbabwean volunteer named Kembo Magonyo

would spend the spring months clearing stubborn jumbles of branches

near the thickly forested border with Mozambique. Wildfires tend to

leap between the two countries, laying waste to trees before anyone

can respond. “This whole bush can be razed to the ground if we don’t

do what we’re doing,” Magonyo says, hacking away with his machete.

His work is organized by a group partly funded by Total’s

carbon-neutral deal.

In the complicated new math of climate solutions, villagers clearing

brush in southern Africa can end up redefining networks of global

commerce worth billions of dollars. Environmental projects stand as

shadow partners to emission-heavy energy trades happening far away.

What Total’s gas cargo puts into the atmosphere, the

machete-wielding villagers will remove. That’s the theory.

Explore dynamic updates of the earth’s key data points

Open the Data Dash.

But to make it work Total’s pioneers of carbon neutrality first

needed to find green projects capable of meeting two requirements:

generate carbon credits backed by an international organization,

without costing too much. After struggling to come up with an

answer, the team set up a meeting with South Pole, a project

developer based in Zurich that came recommended by rival traders.

That’s how $600,000 from a $17 million LNG transaction ended up, in

part, paying for forest protection in Zimbabwe.

The resulting trade looks like a win for everyone. Total kept its

promise to investors to shrink its carbon footprint. Impoverished

communities received financial support. And the buyer, China

National Offshore Oil Corp., cited the shipment as one of the steps

it’s taking to “provide green, clean energy to the nation.” But

climate experts and even a crucial organizer behind the deal say it

will do virtually nothing to decrease carbon dioxide in the

atmosphere, falling far short of neutral.

“The claim that you can market the sale of fossil fuels as carbon

neutral because of a meager few dollars you put into tropical

conservation is not a defensible claim,” says Danny Cullenward, a

Stanford University lecturer and policy director at CarbonPlan, a

nonprofit group that analyzes climate solutions for impact.

At best, Cullenward says, efforts to prevent deforestation by

stopping wildfires can only avoid additional heat-trapping gas

released when trees burn. Rural villagers can’t do anything to

counteract the large-scale pollution from natural gas, other than

making energy traders and consumers feel good for supporting green

causes in regions where money is scarce.

Total said in a statement that it conducts due diligence on offset

projects and confirmed that it split the cost of offsets in the LNG

transaction with Cnooc. The French company declined to discuss

details, including prices paid for carbon credits, citing a

non-disclosure agreement. Cnooc didn’t respond to requests seeking

comment. Total also said it doesn’t count carbon credits in its

companywide emissions reports or as part of its plan to reach net

zero by 2050. “While an important tool,” the company said,

“offsetting cannot be considered as a substitute for direct

emissions reductions by corporates, but as a complement.”

Energy Giants Sell

'Carbon Neutral' Natural Gas That Doesn't Exist

WATCH: Energy Giants Sell 'Carbon Neutral' Natural Gas That Doesn't

Exist

The use of scientifically defined terms like “carbon neutral” and

“net zero” in marketing language introduces additional confusion.

Both terms mean balancing any emissions added to the atmosphere with

an equivalent amount of removal. Most experts agree that avoiding

deforestation isn’t the same as removing greenhouse gases. “This

paradigm,” warns Cullenward, “is encouraging a fictitious engine

that doesn’t help advance our net-zero goals.”

That view isn’t reserved for outside critics. The leader of South

Pole, which helped develop the Zimbabwe project and sold its carbon

credits to Total, doesn’t believe forest protection can rectify

pollution from natural gas. “It’s such obvious nonsense,” says Renat

Heuberger, co-founder of South Pole. “Even my 9-year-old daughter

will understand that’s not the case. You’re burning fossil fuels and

creating CO₂ emissions.”

By safeguarding forests

from the flames, Carbon Green Africa says its volunteers are storing

carbon dioxide in the form of trees.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

Total’s product started warming the planet at the moment of

extraction from the deep-sea Ichthys field off the Australian coast.

Every part of its lifecycle generated greenhouse gas. Sending the

gas to an export facility through an 890-kilometer (553-mile)

pipeline risked leakage of methane, a powerful pollutant that traps

80 times more heat than CO₂ in its first two decades. Chilling the

gas into a liquid for shipping wrought additional emissions. Even

the tanker that brought the LNG to Shenzhen in southern China burned

some of the fuel while sailing.

At the final destination, after Cnooc claimed the cargo last

September, the LNG was likely burned to power the city’s countless

factories or an electricity grid serving more than 12 million

people. This would leave a centuries-long residue of atmospheric CO₂

that Total’s traders had to neutralize. But how much? Total and

Cnooc agreed to set the shipment’s emissions at 240,000 metric tons

of CO₂, the same amount of pollution generated by 30,000 U.S.

households in a year.

The Ichthys LNG terminal in Darwin,

Australia, one of the first steps in the long journey made by

Total’s supposedly ‘carbon neutral’ natural gas.

Source: Copernicus Sentinel-2 Satellite Image; Sept. 11, 2020

The figure is, at best, a rough estimate

since there are too many variables. “No one has convincingly

produced an accurate calculation,” says Fauziah Marzuki, an analyst

at research group BloombergNEF. “All of these deals are making

assumptions.”

If Total’s team started out as rookies at carbon math, South Pole’s

experts arrived as old hands. The company has been generating

credits for more than 15 years—long before the corporate world took

interest in their emissions-erasing power—and today operates in

dozens of countries. Over virtual meetings, according to people

familiar with the transaction, South Pole’s sales representatives

laid out options. The cheapest offsets they had were tied to support

for renewable energy projects, while the most expensive helped fund

reforestation efforts to plant new trees.

Enough carbon credits to offset a shipment of LNG can cost anywhere

between $1 million to $15 million, according to Eurasia Group, a New

York-based think tank. Most trades fall on the lower end of the

spectrum, in terms of cost and quality. Traders in Asia who have

participated in similar deals say the offsets involved usually sell

for less than $6 per ton of CO₂.

“We’ve been hearing low single digits,” in terms of what companies

pay per ton, says Lucy Cullen, an analyst with energy consultant

Wood Mackenzie Ltd. “It makes sense from a commercial standpoint.”

By comparison, Bill Gates said in an interview earlier this year

that he pays about $600 a ton to suck carbon out of the air using

cutting-edge technologies, as a way to offset his personal carbon

footprint.

Pollution Breakdown

Combustion makes up the lion's share of emissions in the LNG value

chain

Source: BloombergNEF

Total decided to source the bulk of its offsets from the Hebei

Guyuan Wind Farm Project, located in a Chinese steel-making province

surrounding Beijing. A similar logic linked the wind farm and the

forest-fire prevention in Zimbabwe. In this case the electricity

generated by the wind turbines would theoretically avoid use of

Hebei’s dirty coal-fired power plants. The resulting reduction in

emissions, compared to an alternative scenario in which only coal

electricity had been used, would form the basis for neutralizing

Total’s gas deal.

Total chose to add additional credits from the project in Zimbabwe’s

Kariba region, which South Pole co-developed with Carbon Green

Africa. Those credits cost more than those from the Chinese wind

farm but on average amounted to less than $3 a ton, according to the

people familiar with the deal. Total declined to comment, citing the

non-disclosure agreement.

Hebei is a steel-making Chinese province

just north of Beijing where coal power plants operate alongside wind

turbines.

Photographer: Yang Shiyao/Xinhua/Getty Images

Did the money from the deal help lower emissions in China? The Hebei

wind farm has been generating clean energy for over a decade, and

it’s unlikely it would have ceased doing so without several hundred

thousand dollars from Total and Cnooc, says Gilles Dufrasne, policy

officer at nonprofit Carbon Market Watch.

Verra, the organization that certified the Hebei credits used in the

Total deal, has since updated its policies to exclude large-scale

grid-connected renewables. If the wind farm’s operators tried to

register as an offset project today, “it would not be accepted,”

says Dufrasne.

When climate scientists think about offsets, a key concept they

grapple with is called “additionality.” You only balance the carbon

scale if you actually remove CO₂ that wouldn’t have been absorbed

without your support. It’s an extremely tricky concept that’s prone

to abuse. After all, how do you prove that something worse would

have happened if you hadn’t intervened?

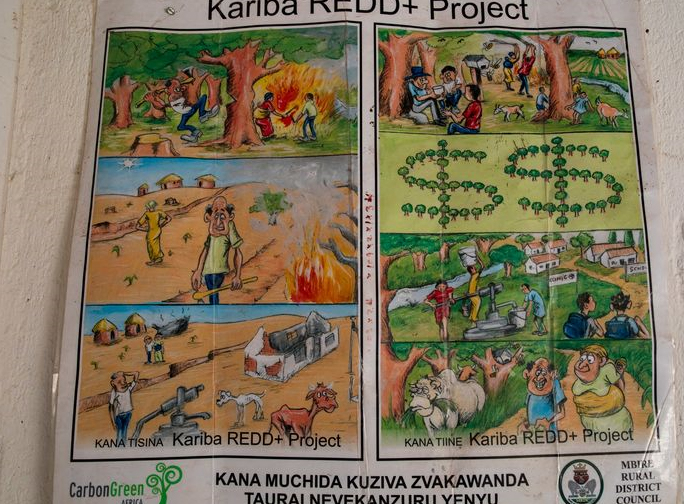

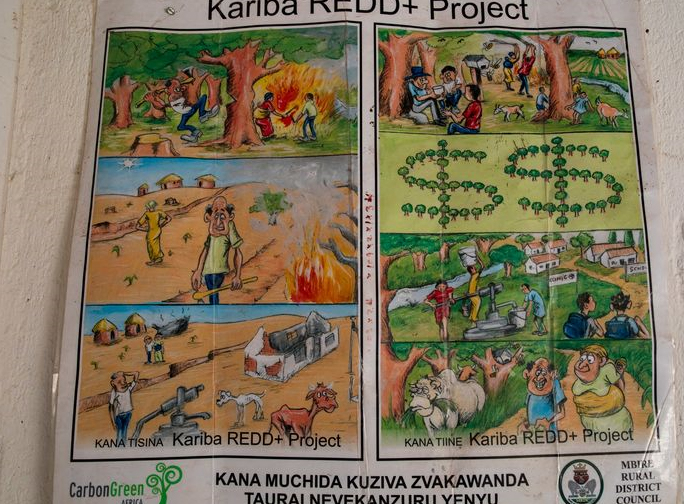

Carbon Green Africa, the organizer of the Zimbabwe effort backed by

South Pole and Total, is working to defend a 785,000-hectare

wildlife corridor across four provinces. Volunteers are told that

keeping fires at bay is about more than protecting crops and

livestock. It’s part of a global mission to arrest global

temperatures. By safeguarding forests from the flames, the project

is supposed to be keeping CO₂ stored in the form of trees.

But projects like this have become a point of contention. They’re

based on a framework known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation

and Forest Degradation (REDD+), a program started under the auspices

of the United Nations. The initial goal was to help governments

trade offsets with each other so that rich countries might

financially support climate action by developing nations. After

political leaders couldn’t agree on how the system should work,

project developers started marketing the offsets directly to

corporations.

Even if work to combat deforestation can’t counteract an LNG

shipment, corporate patronage has helped improve life in Mbire, one

of the districts in Zimbabwe that’s home to volunteers in the

forest-protection project. More than a dozen residents spoke

positively about the program during a visit by a Bloomberg Green

reporter earlier this year.

Theresa Mutseura, a health administrator at the Chitsungo Mission

Hospital, said the project helped set up a biogas digester to power

the 65-bed facility. The only hospital in a region with 33,000

people and just two doctors had previously relied on firewood.

Zvionere Chaku, 43, said volunteers with Carbon Green taught her how

to farm more expensive vegetables in a small garden rather than

clearing land.

Zvionere Chaku tends to a vegetable garden

in Mbire, Zimbabwe.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

Benefits of the program can be measured.

The region lost about 0.23% of its tree cover between 2011 and 2020,

according to analysis of satellite images by Global Forest Watch,

compared with a rate of 0.65% before the project began. Economic

growth has also been stronger in the districts covered by the

project compared with similar areas, according to gross domestic

product figures provided by the local government.

Last year Carbon Green paid Z$215 million ($2.5 million) to Mbire,

with the bulk of the funding going to infrastructure projects such

as roads and schools that help boost development. About 20% goes

directly to environmental protection. “The money was a windfall,”

says Tarcisius Mahuni, who runs the local district council from an

office decorated in posters for the REDD+ program. The funds from

carbon credits were more than triple what local officials had hoped

to collect in tax revenue.

Theresa Mutseura works at the Chitsungo

Mission Hospital, the only facility serving a population of 33,000.

Internet connectivity is so bad that the physicians sometimes have

to leave mid-procedure to look up medical information online.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

Mbire’s improving infrastructure must also contend with impacts from

warming temperatures, made worse by the use of fossil fuel. “We have

had droughts, floods, cyclones, hunger and diseases,” says Charles

Ndondo, Carbon Green’s managing director who oversees local

operations. “If I was not worried about climate change, I would not

be running this project.”

This puts on display an uncomfortable truth about the global climate

movement: powerful multinational companies can essentially outsource

the cleanup of their pollution to faraway places in need of help for

a fraction of their profits. Doing so is far cheaper than direct

means of removing pollution from their businesses. Carbon Green says

the project in Zimbabwe avoids 6.5 million tons of carbon emissions

each year while getting, at most, $1.50 per ton; sometimes the group

gets paid as little as $0.20.

Heuberger, the co-founder of South Pole, stands by the sale of

credits to support the work in Zimbabwe. But it troubles him that

Total is using offsets to market natural gas as carbon neutral. His

company tells clients they should use such offsets to “take

responsibility” for their emissions, not to make claims that they

have neutralized ongoing pollution. In a statement, Total said South

Pole never raised objections over using the term “carbon neutral.”

In a way, it comes down to semantics. As corporate climate action

grows more complex, so do the norms around net-zero goals. There’s

growing consensus among top companies that the cheap and abundant

credits used by Total—called avoided emissions offsets—should not be

used to claim progress towards net zero. That’s why executives are

increasingly turning to the phrase “carbon neutral” as a compromise.

The term is gaining cache as a way for companies to take credit for

supporting environmental projects, even if they haven’t actually

removed CO₂ from the atmosphere.

Paltry Offering

Less than 5% of offsets actually remove carbon dioxide from the

atmosphere

Source: TSVCM inventory analysis for 2020

Note: Avoided emissions credits prevent hypothetical polluting

activity

Scientists warn that “net zero” and “carbon neutral” are technical

terms and diluting their meanings in marketing campaigns could have

a disastrous impact on the global effort to account for emissions

and reduce greenhouse gas.

The nuance isn’t lost on Heuberger. The 44-year-old Swiss social

entrepreneur has spent almost half his life working on environmental

conservation projects in developing countries. It’s been an uphill

battle to secure funding for the programs, and Heuberger is grateful

for every dollar companies put into South Pole’s projects. It makes

sense to him that firms want to tout their environmental

contributions, especially to worthy efforts to help improve life for

African villagers.But he says the idea that such contributions can

make up for selling fossil fuels will do more harm than good. They

risk undermining the projects themselves, especially as scrutiny of

carbon offsets increases. “These claims are damaging ourselves as

well,” Heuberger says.

That’s in part why well-regarded registries such as Gold Standard

don’t certify offsets from most REDD+ projects, and many experts

including the Science-Based Targets initiative disapprove of using

offsets based on avoided emissions to make net-zero claims. It’s

possible to claim that some trees are standing today that might have

been lost without brush clearing. But it’s just not possible to

establish that extra carbon was removed from the atmosphere.

Posters advertising local REDD+ projects line the office walls of

Tarcisius Mahuni, who runs the local district council.

Photographer: Cynthia Matonhodze/Bloomberg

Total is writing its own tale on the

strength of its first-ever sale of carbon-neutral LNG. It’s the

transformation of an old-school energy behemoth into a clean

supermajor.

The company spent the last decade investing billions to position

itself as one of the world’s top LNG producers and has green-lit new

export projects from Russia to Mozambique that are slated to begin

operations this decade. For the last 60 years, natural gas has been

viewed as a cleaner alternative to coal and crude oil. That’s given

companies like Total confidence in its longevity, even in an era of

unprecedented climate action.

That future is looking more and more uncertain. The price of solar

and wind energy is falling much faster than anyone expected. There’s

growing awareness of the climate dangers from leaky pipelines used

to transport the gas, which can release large amounts of methane,

the super-potent greenhouse gas that’s the main component of LNG.

The latest assessment published this week by UN-backed scientists

calls for reducing methane emissions in the next 10 years if the

world is to meet its climate goals.

The International Energy Agency recently put forward a timeline for

keeping global temperatures from rising more than 1.5° Celsius above

pre-industrial levels. The use of natural gas would have to fall by

more than half its current level, meaning no new gas fields or

export terminals should be built from now on.

As a European company, Total is in an awkward position as the

continent’s politicians advance the world’s most-ambitious package

of climate policies. The goal is cutting emissions 55% from 1990

levels by the end of the decade. Total Chief Executive Officer

Patrick Pouyanne said in July that the company would probably aim to

accelerate efforts to cut all its emissions, in line with the

European Union, if those aggressive climate measures are

implemented. In a sign of this shift, Total recently added

“Energies” to its name to highlight the increasing share of its

business that has nothing to do with fossil fuels.

Even as those changes are underway, Total and its peers in Europe

are working to bolster demand for their core product. Labeling LNG

shipments “carbon neutral” is one way to satisfy customers who are

under pressure from their investors and governments to cut

emissions. At least 16 carbon-neutral shipments have changed hands

since 2019, and there’s a push from buyers and sellers to do more

deals. This is especially true in Asia where two of the world’s top

importers—Japan and China—have set targets to zero out emissions.

Asian Demand

Most shipments since July 2019 have gone to Asia

Source: BloombergNEF

None of the energy companies involved have disclosed the math behind

their carbon-neutral claims, and there’s no requirement that they do

so. While Total says it won’t erase emissions from the LNG shipment

it sold to Cnooc from its carbon accounts, there’s no guarantee that

Cnooc will take the same approach. The Chinese state-owned company

has described the gas shipment as “net-zero carbon emissions” and

has indicated that it will rely on similar deals to meet President

Xi Jinping’s goal of reaching net zero by 2060. The trade was a

“pioneering case in China's natural gas industry to explore

carbon-neutral practices,” Cnooc said in a press release announcing

the LNG delivery from Total.

This sets a troubling precedent, says Arvind Ravikumar, an assistant

professor at Harrisburg University of Science and Technology in

Pennsylvania who studies sustainable development. A

nature-conservation project without clear carbon benefits could be

used to cancel out emissions for both Cnooc and China, the world’s

single biggest polluter.

The credits “help them remove emissions from their annual report on

paper without actually ensuring that the amount of emissions gets

removed from the atmosphere,” Ravikumar says. “It seems like they

have all fallen into the trap of finding the quickest and cheapest

way to appear to do something.”

—With assistance from Karoline Kan and Francois De Beaupuy

A resident flees the village of Gouves, on

the island of Evia, Greece, on Sunday, Aug. 8, 2021. Elevated risk

of fires is just one of the effects of climate change being felt all

over the world.

Photographer: Konstantinos Tsakalidis/Bloomberg

Climate Scientists Reach ‘Unequivocal’

Consensus on Human-Made Warming in Landmark Report

The first major assessment from the UN-backed Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change in nearly a decade sees no end to rising

temperatures before 2050.

By Eric Roston and Akshat Rathi

August 9, 2021, 1:00 AM PDT Updated on August 9, 2021, 3:59 AM PDT

An epochal new report from the world’s top climate scientists warns

that the planet will warm by 1.5° Celsius in the next two decades

without drastic moves to eliminate greenhouse gas pollution. The

finding from the United Nations-backed group throws a key goal of

the Paris Agreement into danger as signs of climate change become

apparent across every part of the world.

The latest scientific assessment from the UN’s Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change for the first time speaks with certainty

about the total responsibility of human activity for rising

temperatures. The scientists forecast no end to warming trends until

emissions cease.

“It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere,

ocean and land,” wrote the authors of the IPCC’s sixth global

science assessment since 1990 and the first released in more than

eight years. The crucial warming threshold of 2°C will be “exceeded

during the 21st century,” the IPCC authors concluded, without deep

emissions cuts “in the coming decades.”

Scientists Reach ‘Unequivocal’ Consensus on Climate Change

Scientists Reach ‘Unequivocal’ Consensus on Climate Change

The assessment released on Monday is the work of more than 200

scientists digesting thousands of studies, and an accompanying

summary was approved by delegates from 195 countries. More than any

other forecast or record, this report’s determinations establish a

powerful global consensus—less than three months before the UN’s

COP26 international climate talks.

Among the headline findings: The past decade was most likely hotter

than any period in the last 125,000 years, when sea levels were as

much as 10 meters higher. Combustion and deforestation have also

raised carbon dioxide in the atmosphere higher than it’s been in two

million years, according to the report, and agriculture and fossil

fuels have contributed to methane and nitrous oxide concentration

higher than any point in at least 800,000 years.

The full, 3,949-page assessment was released in conjunction with the

42-page “summary for policymakers.” While the latter went through a

diplomatic approval process in addition to a scientific one, the

former comes directly from scientists. Chapter one of the underlying

report includes strong language admonishing Paris signatories,

calling their pledges so far under the agreement “insufficient to

reduce greenhouse gas emission enough” to keep global warming well

below 2°C.

The document is “a code red for humanity,” said Antonio Guterres,

secretary-general of the United Nations, in prepared remarks tied to

the release. “This report must sound a death knell for coal and

fossil fuels before they destroy our planet.”

Heat Spike

Humanity has heated the climate to at least a 100,000-year high. All

of the warming is caused by human influence.

Source: IPCC AR6 Working Group I report

Note: Diagonally shaded areas show 90%–100% certainty range

Even as the IPCC authors have done away with some of the cautious

uncertainty that marked past assessments, the last few months have

seen a series of rapid-fire climate disasters that underline the new

language. Summertime in the Northern Hemisphere has been marred by

severe flooding across Europe and China, as well as alarming drought

and the early onset of large wildfires in the Western U.S. and

Canada. One of the coldest places on the planet, Siberia, has

experienced severe heat and forest fires. Just this past weekend

brought disturbing footage of people fleeing sprawling wildfires in

Greece.

Nearly all of this can be attributed to human influence. The IPCC

found that the combined effects of human activity have already

increased the global average temperature by about 1.1°C above the

late 19th-century average. The contribution to global warming of

natural factors, such as the sun and volcanoes, is estimated to be

close to zero. In fact, humans have dumped enough greenhouse gas

into the atmosphere to heat the planet by 1.5°C, according to the

report, but fine-particle pollution from fossil fuels provides a

cooling effect that masks some of the impact.

Read More:

• There’s Already Enough Greenhouse Gas in the Air to Heat the

Planet by 1.5°C

• Major New Climate Report Puts Pressure on COP26 to ‘Consign Coal

to History’

• Five Key Takeaways From the Latest IPCC Report on Climate Change

• Stop Warming? First, Focus on the Rules: Opinion Digest

• Inside the Showdown Between UN Climate Science and Global Politics

• This Is Why Even Scientists Underestimate Climate Change

In its fifth assessment, published in 2013, IPCC’s volunteer

scientists introduced the idea of a “carbon budget,” setting an

upper bound on the amount of carbon dioxide that can be added to the

atmosphere before it will breach certain temperature thresholds.

“Now we have much more confidence in those numbers,” said Joeri

Rogelj, a lecturer in climate change and the environment at Imperial

College London and one of the report’s authors.

Humanity will have about a 50% chance of staying below the 1.5°C

threshold called for by the Paris Agreement if CO₂ emissions from

2020 onwards remain below 500 billion tons. At the current rate of

emissions, that carbon budget would be used up in about 13 years. If

the rate doesn’t come down, the planet will warm more than 1.5°C.

“Our opportunity to avoid even more catastrophic impacts has an

expiration date,” said Helen Mountford, vice president of climate

and economics at the World Resources Institute. “The report implies

that this decade is truly our last chance to take the actions

necessary to limit temperature rise to 1.5°C. If we collectively

fail to rapidly curb greenhouse gas emissions in the 2020s, that

goal will slip out of reach.”

Hitting the Limit

No single number captures the remaining CO2 budget. Estimates assume

different warming levels and odds of meeting them

Source: IPCC AR6 Working Group I report

Note: The higher and lower numbers in each budget scenario represent

17% and 83% chances of staying under each temperature limit. The

world emitted 34 Gt of CO2 in 2020

The new publication lands in the middle of the ramp-up to COP26, to

be held in Glasgow in November. A global deal to pursue faster

emission cuts would depend on poor countries securing $100 billion a

year in climate finance from rich countries, something envisioned in

previous climate agreements but not yet achieved. National

governments would also need to agree to rules governing the trading

of emissions permits, to ensure those moving faster towards cuts are

rewarded for doing so.

Unlike the IPCC’s somewhat anomalous 2018 special report, Global

Warming of 1.5°C, the publication released Monday doesn’t explicitly

state that net-zero emissions must be achieved by 2050 to meet the

goals set out in the Paris Agreement. That’s because this group’s

mandate was to assess new scientific knowledge, not prescribe policy

actions. Upcoming IPCC assessments expected next year in February

and March will address climate impacts, adaptation and mitigation.

The authors of the new IPCC publication add that, after accounting

for global emissions since the 2018 special release, its estimate of

the world’s remaining carbon budget is “of similar magnitude” to the

one in its prior publication, implying that the finding stands. This

latest assessment’s most ambitious scenario shows emissions falling

to net zero around 2050, which is as close as it comes to restating

the top-line conclusion of the special report.

All five of the new report’s temperature scenarios show the 1.5°C

marker passed by 2040, before cooling down below that mark in only

one of five scenarios. Achieving that cooling will depend on

large-scale removal of carbon dioxide from the air. An independent

analysis conducted by the group Climate Action Tracker suggests that

current global policies may track either the IPCC’s medium or high

scenarios, which lead to 2.7°C and 3.6°C of warming by 2100.

New Scientific Tools Enter the Mainstream

The climate science profession has seen entire specialties

emerge and mature in the years since the IPCC’s previous mega-report

on science. None of these is more resonant than the ability to

analyze extreme weather events in real-time to determine the role of

climate change.

Twenty years ago, researchers couldn’t link a specific weather event

directly to human-made climate change, meaning that the scientific

likelihood of a specific storm or heat wave being tied to warmer

temperatures wasn’t knowable. Today, many of these weather

attribution studies can be produced within days or weeks of an

event.

The deadly heat wave that gripped the western coast of North America

in June had detectable evidence of human responsibility. World

Weather Attribution, an international research group, needed just

days after the heat broke to conclude that the extraordinary

temperatures would be “virtually impossible” without climate change.

This ability of scientists to parse the probability that any one

disaster is driven by warming temperatures highlights one of the

IPCC’s core findings: The entire globe is warming, although not

uniformly. Regions will still experience natural swings in

temperature, particularly in coming years, as it takes time for

heating to have a significant effect on the Earth’s processes.

A World of Change

The entire globe is undergoing changes, some unprecedented in

thousands or hundreds of thousands years

Source: IPCC AR6 Working Group I report

Another research breakthrough in the field of climate sensitivity

now allows scientists to make even more confident projections about

future warming. Drawing from research on ancient climates, as well

as advanced satellite technology that monitors clouds and emissions,

IPCC authors were able to narrow their temperature projections for

the rest of the century, giving humanity a clearer picture of what

lies in store if we don’t act quickly to curtail emissions.

The Earth’s response to a theoretical doubling of preindustrial CO₂

levels is now thought to be between 2.5°C to 4°C—a much smaller

range than 1.5°C to 4.5°C in previous IPCC reports. “The top end is

being reduced, which means that some of these really bad outcomes,

where we roll sixes on the climate sensitivity dice, seems a little

less plausible than they did,” said Zeke Hausfather, director of

climate and energy at the Breakthrough Institute, who wasn’t an

author of the summary.

This development helped the IPCC authors cope with another headache:

Some Earth-system models updated for this assessment began showing

surprisingly high projections for future warming. But the

breakthrough allowing greater confidence in the Earth’s potential

response to CO₂ gave scientists welcome evidence to balance the

modeling approach with other research.

Methane escaping from melting permafrost

can have a much greater warming effect than CO₂.

Photographer: Michael Robinson Chavez/The Washington Post/Getty

Images

The improvements in projections came, in

part, from a stronger grasp of so-called “climate feedbacks” such as

the way melting ice and greenhouse gases escaping from thawing

permafrost compound on each other in previously unpredictable ways.

Scientists are now more confident that lowering emissions will mean

less chance of activating feedbacks. That also means that the

actions humanity takes in the near term to limit emissions will be a

determining factor in whether we see these dramatically accelerating

effects in the longer term.

The IPCC’s new findings rule out the

possibility that unrestricted emissions will have only a mild effect

on global temperatures, a hope few if any observers were still

clinging to. But the updated science, particularly the narrowed

range for climate sensitivity, provides powerful evidence of the

world’s best pathway to safety: swiftly ending the release of carbon

dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

What Comes Next?

There is an endgame, if nations choose to try and reach it. The data

continue to show a straightforward relationship between CO₂ and

temperature. That means that when atmospheric carbon concentrations

stop rising, the temperature will, too, soon thereafter.

Scientists have broken ground by projecting what happens when our

emissions cease. As the world reduces its use of fossil fuels, for

instance, the cooling effect of aerosols will start to decline.

Scientists are confident that one way to counter that decline would

be to pursue “strong, rapid and sustained reductions” in methane

emissions. Beyond CO₂, methane, and nitrous oxide, there are four

other greenhouse gases that also provide opportunities to slow

warming.

Greenville, California, an Indian Valley

settlement of a few hundred people dating back to the mid-1800s Gold

Rush, was decimated by the Dixie fire last week.

Photographer: Josh Edelson/AFP/Getty Images

Even at 1.1°C, climate change is taking

lives and destroying property and forcing retreat, migration and

conflict. The effects of human activity are continuing to melt

glaciers and sea ice. Heating oceans means raising them—at a rate

more than 2.5 times faster in this century than the last, according

to the IPCC. Some of that harm is now baked in for centuries to

come.

“This last year has proven that climate change is no longer a

distant threat,” said Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist at the

Nature Conservancy, who wasn’t involved in the summary. “We can no

longer assume that citizens of more affluent and secure countries

like Canada, Germany, Japan and the United States will be able to

ride-out the worst excesses of a rapidly destabilizing climate, even

as those in more vulnerable latitudes suffer.”

A Path to Safety

An emissions scenario that can keep global warming below 1.5°C

reaches zero emissions around 2050.

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

In a press conference Monday morning, IPCC leadership emphasized

that the disparate effects of climate change are being felt in every

region of the world. The new report also comes with an interactive

tool that enables users to apply its underlying datasets to the

world map. That could, for example, help India reckon with the

impact warming could have on economically crucial rainfall patterns

under different emissions scenarios.

“When we put everything together, for almost all of the 44 regions

in the world, coastal climate impact drivers were increasing,” said

Roshanka Ranasinghe, professor of climate change impacts and coastal

risk at the University of Twente and one of the authors of the

assessment.

The IPCC is inherently conservative. It emphasizes information in

which scientists have the most evidence and agreement. At the same

time, the new scientific consensus doesn’t rule out continued

investigation of its lower-confidence findings. The authors indicate

that some potentially sweeping changes are not as well understood,

such as unlikely but still possible heat extremes or ice-sheet

collapse.

Another “low-likelihood high-impact outcome” flagged by IPCC authors

is a sudden, dramatic change in ocean circulation. A study released

last week in the journal Nature Climate Change documented changes in

the powerful churn of Atlantic water as potential indicators of “an

almost complete loss of stability.”

The IPCC itself foresees further weakening of the Atlantic

Meridional Overturning Circulation in the decades ahead, with

disagreement over the possibility of collapse before 2100. Such an

event would weaken monsoons in Africa and Asia, strengthen them in

the Southern Hemisphere and dry out Europe.

There are always more questions to ask, and the perpetual churn of

research means even the most comprehensive assessment can never be

truly complete. “That’s just what science is, right?” said Tamsin

Edwards, an IPCC author and a reader in climate change at King’s

College London. “It’s constantly evolving and refining and adding

new studies, and improving our knowledge. The intensity of the

effort that goes into assessing the literature—the 14,000 papers for

this report—makes it an authoritative, comprehensive, coherent

synthesis in a way that a single paper can never be.”

— With assistance from Dave Merrill and Mira Rojanasakul

(Adds a new sixth paragraph to incorporate material from the IPCC’s

full report. Also adds a new 30th paragraph on the group’s

interactive mapping tool and quote from Roshanka Ranasinghe.)

(Adds a new sixth paragraph to incorporate material from the IPCC’s

full report. Also adds a new 30th paragraph on the group’s

interactive mapping tool and quote from Roshanka Ranasinghe.)

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

exactrix@exactrix.com

|