|

Inside Climate News

Clean

Energy

Overwhelmed

by Solar Projects, the Nation’s Largest Grid Operator Seeks a Two-Year

Pause on Approvals

“It’s a kink in the system,” says one developer trying to bring solar

jobs to coal country. “The planet does not have time for a delay.”

By

James Bruggers

Power lines in West Reading,

Pennsylvania, February 2021. Credit: Ben Hasty/MediaNews Group/Reading

Eagle via Getty Images

“It’s a kink in the system,”

said Adam Edelen, a former Kentucky state auditor who runs a company

working to bring solar projects and jobs to ailing coal communities in

Appalachia, including West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia and

Kentucky. “Anyone paying attention would acknowledge that this has a

tremendous impact on climate policy and energy policy in the United

States.”

The backlog at PJM is a

major concern for renewable energy companies and clean energy

advocates, even though grid operators are a part of the energy economy

that is largely unknown to the public.

“There is broad national

consensus, in the leadership from the public and the private sector,

that we need to hasten the adoption of renewable energy,” Edelen said.

“The planet does not have time for a delay.”

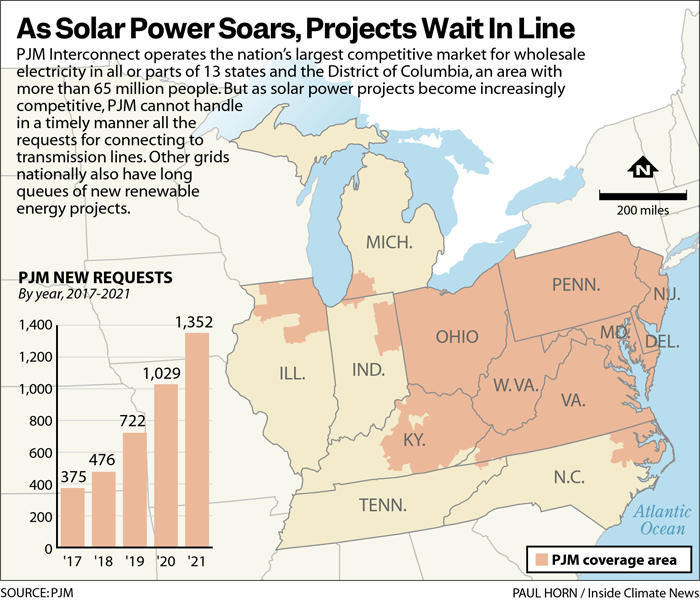

PJM, a nonprofit, operates a

competitive market for wholesale electricity in all or part of 13

states and the District of Columbia, including Pennsylvania, West

Virginia and Kentucky—but one without a lot of renewable energy. Wind,

solar and hydropower plants make up about 6 percent of its

distribution mix.

Over the last four years,

PJM officials said they have experienced a fundamental shift in the

number and type of energy projects seeking to be added to a grid that

extends from Virginia to northeast Illinois, each needing careful

study to ensure reliability.

In the past, PJM’s energy

project queue was dominated by a few large projects like big natural

gas power plants. Now, PJM officials said, they are receiving a

proliferation of smaller projects, each needing study.

“Our system wasn’t designed

to handle that kind of growth,” said Kenneth S. Seiler, vice president

of planning at PJM.

About 2,500 projects are

awaiting action by the grid operator, which is based in Valley Forge,

Pennsylvania, outside Philadelphia.

PJM officials are proposing

a two-phased solution.

They want to move to a new

approval process that puts projects that are the most ready for

construction at the front of the line, and discourages those that

might be more speculative or that have not secured all their

financing.

PJM officials said they have

reached a reasonable consensus among their members for that plan.

However, they are also

proposing an interim period with a two-year delay on about 1,250

projects in their queue, and a deferral on the review of new projects

until the fourth quarter of 2025, with final decisions on those coming

as late as the end of 2027.

“We are taking a pause,”

Seiler said of the grid operator’s proposal. “We are refining the

process to deal with these smaller types of projects. We will catch

up.”

The United Nations

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change last summer

issued the first installment of its latest global warming

assessment, prompting UN Secretary-General António Guterres to

describe

the work as nothing less than “a code red for humanity.”

Still, Seiler said he’s not

certain whether PJM can attain the Biden goal of achieving 100 percent

carbon-free electricity by 2035. PJM in December

announced a study looking at how it could boost renewable energy

mix to 50 percent by 2035. With nuclear energy in the region factored

in, that could get the PJM grid to about 60 to 70 percent carbon free,

he said.

“We’re not sure, frankly,

quite yet, because we’re still studying it, if we can get there, 100

percent renewable by 2035,” Seiler said. “But I can tell you, we’re

taking a real hard look at it.”

“The Process Right Now Is

Effectively Broken”

PJM has established a

task force to work its proposal through committees of its members,

including electric utilities and energy developers. By May, officials

hope to submit it to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which

has final say.

With so much money at stake

in a policy with the potential to help make financial winners and

losers, experts say they expect whatever FERC decides may end up in

court.

National studies show grid

operators across the country have a growing queue of energy projects,

many that do not pan out and actually clog up the system. In 2021, the

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

found that only 24 percent of projects nationally seeking

connection from 2000 to 2015 were built, and completion percentages

since then appeared to be declining.

Last year, Americans for a

Clean Energy Grid, a national group advocating for modernization of

high voltage transmission, made the case in a

report that backlogs were “needlessly increasing electricity costs

for consumers by delaying the construction of new projects which are

cheaper than existing electricity production. Because most of these

projects are located in remote rural areas, this backlog is harming

rural economic development and job creation.”

How PJM resolves its backlog

could have implications for the rest of the country, said Jeff Dennis,

managing director and general counsel for Advanced Energy Economy, a

trade group for clean energy businesses.

“PJM has traditionally been

a bellwether,” he said. “Things that PJM puts into place and that FERC

approves for PJM often become models for other regions,” he said.

A lot is at stake, he added.

“Delayed interconnection

queues and backlogs in bringing new generation on is one of the most

significant barriers to state clean energy policies and the jobs and

economic development that states are aiming to achieve through

transitioning their grids to advanced energy technologies,” he said.

But “folks should be

encouraged that there was wide stakeholder support for many, many

aspects of PJM’s still-developing generator interconnection process,”

Dennis said.

PJM’s efforts to cope with

and efficiently manage the backlog have the support of Justin Vickers,

staff attorney for the Environmental Law & Policy Center, a

Chicago-based environmental advocacy group.

“I hear from developers all

the time that PJM’s queue is such a mess that it’s putting their

ability to get projects done in jeopardy, and it’s creating

uncertainty in getting projects up and running,” he said. “Trying to

find a way out of this mess is good.”

He compared what PJM is

doing with traffic metering lights at freeway onramps. “What it’s

actually doing is managing the congestion to smooth things out. It

feels like you should just get there as fast as you can. You shouldn’t

have to pause in order to get on the highway. But actually it’s better

for everyone if you do, even if it might be slightly worse for you,

the individual traveler.”

Ohio-based utility AEP has,

within the PJM territory, wind and solar projects proposed for

Virginia and is also seeking to add renewable energy to its mix in its

Indiana Michigan Power territory, said company spokeswoman Tammy

Ridout. She said company officials expect those projects “are largely

already in the PJM queue.”

She said AEP supports “the

changes that PJM is putting in place to help improve the process,

including prioritizing projects that have financing and other key

aspects secured so those can move forward first.”

At PJM and other grid

operators across the country, “the process right now is effectively

broken,” said Gizelle Wray, senior director of regulatory affairs and

counsel for the Solar Energy Industries Association, a trade group.

While she acknowledged that

some of the association members are happy with what PJM has proposed,

she said that others are not, adding: “This is as fair of an outcome

as we could possibly get.”

Solutions are needed beyond

what PJM has proposed, she said, adding that the association hopes

FERC will move the country toward better transmission and

interconnection policies.

“We need solutions that make

sure this doesn’t happen anymore,” Wray said.

A FERC spokesman did not

return requests for comment.

Coal Communities Need

Investment

The length of the PJM

backlog varies by state. For example, in Pennsylvania, where Gov. Tom

Wolf in 2019 set his state’s first statewide greenhouse gas reduction

goals, 520 energy projects are currently in the queue, 437 of which

are solar. Virginia, which adopted powerful renewable energy portfolio

standards for electric utilities in 2020, has 417 solar projects in

the queue. Kentucky and West Virginia have been slow to adopt solar

but those states have 110 and 57 solar projects, respectively,

awaiting approval by PJM.

In Kentucky, Edelen ran for

governor in 2019 in part on a

platform that the state needed to embrace the reality of climate

change and adapt the state’s coal-dependent economy, but lost in the

Democratic Primary to Gov. Andy Beshear. He said he understands PJM’s

situation and that much of what it has proposed makes sense.

Adam Edelen, former state auditor

during his unsuccessful campaign for Kentucky governor. Credit: John

Sommers II /Special to the Courier Journal

His company, Edelen

Renewables, is a

partner in a 200-megawatt solar project on a former strip mine in

Martin County, Kentucky, that he says is far enough along that it

won’t be affected by PJM rule changes. But in January he

announced

a joint venture with a 200-year-old West Virginia company, The

Dickinson Group, with its extensive land holdings, including mine

sites, that Edelen said could lead to several new solar farms.

He said he fears those

efforts will face years’ long delays as PJM works through its backlog,

and he said he’s frustrated that the transition to a new energy

economy hinges on the actions of a vital but relatively little-known

organization.

In addition to retooling its

approval process, PJM should increase the size of its staff to meet

the demand and urgency for renewable energy, Edelen said.

“Staffing is an issue,”

conceded Seiler.

But Seiler said qualified

engineers would need to be found. And then, he said, “it takes several

years to train somebody to do a lot of this work.”

Edelen said that just as

climate solutions can’t wait, according to the latest science, neither

can coal communities.

“I believe we can fight

climate change and revitalize forgotten American communities,” he

said. “A be-patient approach from (PJM) administrators is not

something I agree with.”

Inside Climate News

reporter Dan Gearino contributed to this report.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

Nathan1@greenplayammonia.com

exactrix@exactrix.com

|