|

Oil Wells Orphaned in North

Dakota Require Federal and State Help. May 23, 2021

Fossil Fuels

North Dakota, Using Taxpayer Funds, Bailed Out Oil and Gas Companies

by Plugging Abandoned Wells

The bailout, environmentalists say, raises bigger questions about who

will pay, in an energy transition, to close off the nation’s millions

of aging wells.

By Nicholas

Kusnetz

May 23, 2021

An abandoned oil well sits on a

farm in Western North Dakota, with contamination spreading into the

field beyond it. Credit: Daryl Peterson

Related

When North Dakota directed more than $66 million in federal pandemic

relief funds to clean up old oil and gas wells last year, it seemed

like the type of program everyone could get behind. The money would

plug hundreds of abandoned wells and restore the often-polluted land

surrounding them, and in the process would employ oilfield workers who

had been furloughed after prices crashed.

The program largely accomplished those goals. But some environmental

advocates say it achieved another they didn’t expect: It bailed out

dozens of small to mid-sized oil companies, relieving them of their

responsibility to pay for cleaning up their own wells by using

taxpayer money instead.

Oil drillers are generally required to plug their wells after they’re

done producing crude. But in practice, companies are often able to

defer that responsibility for years or decades. Larger companies often

sell older wells to smaller ones, which sometimes go bankrupt, leaving

the wells with no owner.

These “orphaned wells” become the responsibility of the federal or

state governments, depending on where they were drilled. While oil

companies are required to post bonds or other financial assurance to

pay for plugging them, in reality those bonds cover only a tiny

fraction of the costs, leaving taxpayers on the hook. One estimate, by

the Carbon Tracker Initiative, a financial think tank, found that

those bonds cover only a tiny fraction of the expected costs of

cleaning up the nation’s oil and gas wells.

“What happened was a bunch of people got a free ride,” said Scott

Skokos, executive director of the Dakota Resource Council, a

grassroots environmental group in the state.

Skokos said it only deepened his sense that the state had bailed out

the industry. In October, regulators were granted permission from

state lawmakers to send about $16 million of the CARES Act funds as

grants to oil companies to help them buy water to hydraulically

fracture new wells, a step the regulators said was necessary to expend

the funds by the end of the year. Nine companies took advantage of the

program. In one case, a single company, Continental Resources,

received $5.4 million, according to state records.

Wyoming also sent about $30 million in Covid relief funds to oil

companies as grants to either frack new wells or revive or plug old

ones.

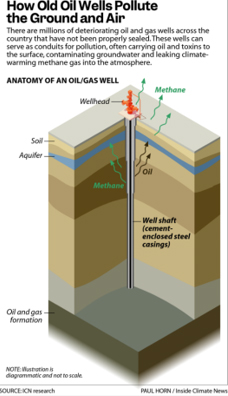

Some advocates say that such well-plugging programs highlight a larger

problem: Millions of aging, unplugged oil and gas wells dot the ground

from Appalachia to California, often carrying oil and toxins to the

surface, contaminating groundwater and leaking climate-warming methane

gas into the atmosphere.

The Environmental Protection Agency estimates that the nation’s

unplugged wells leaked about 263,000 tons of methane in 2019, which,

when compared to carbon dioxide over a 20-year period, is equivalent

to the climate-warming emissions of more than 5 coal-fired power

plants. The agency added that the actual figure could be significantly

smaller or three times greater.

While many of the wells—hundreds of thousands at least—are orphaned,

many more are still operated by oil companies that critics say have

avoided plugging them because of regulations that allow the industry

to postpone cleaning them indefinitely, eventually dumping the

responsibility on taxpayers.

President Joe Biden’s American Jobs Plan calls for spending $16

billion to clean up the nation’s orphaned wells and coal and hardrock

mines, and lawmakers have drafted bills with similar goals.

Environmentalists, leaders in both political parties and

the oil industry all support directing federal dollars to plug

orphaned wells as a way to address climate change and pollution, while

creating jobs for oilfield workers. But some advocates say that what

happened in North Dakota shows the risks of spending billions of

dollars without sufficient scrutiny and without requiring oil

companies to put up more money to pay for plugging their wells.

“There’s an incredible opportunity to begin cleaning up and better

cataloging orphan wells while creating well-paying jobs,” said Sara

Cawley, a legislative representative for Earthjustice, an

environmental nonprofit. But, she said, any federal spending needs to

be tied with regulatory reforms, including requiring companies to set

aside more money for plugging, “so that taxpayers are not continuing

to pay for clean-up in perpetuity.”

Two bills have been introduced so far. Both would direct billions of

dollars to plug orphaned wells on state, federal and tribal lands, and

both include language that would encourage states to improve

well-plugging regulations by tying a portion of the funding to

reforms. Only one, however, by Rep. Teresa Leger Fernandez (D-N.M.),

would require oil companies to purchase more expensive bonds when

drilling on federal land, leaving more money available in case of

default.

Lynn Helms, director of North Dakota’s Department of Mineral

Resources, defended the state’s program from criticism that it bailed

out the industry, saying it targeted companies that were facing

financial stress because of last year’s crash in oil prices, and that

in some cases, small, mom-and-pop operations did not have the funds to

plug the wells. He said his department has begun to pursue

reimbursement from some of the companies that are still solvent, and

has already obtained more than $3 million to reimburse a state

well-plugging fund that covered some costs beyond the $66 million from

the CARES Act.

He said the program served the intent of the CARES Act—to stimulate

the economy and support employment—by creating more than 3,700 jobs,

“and that was the number one purpose for why we did this.”

Helms said the $16 million in grants for fracking was also intended to

support workers and state finances, which are highly dependent on tax

revenues from oil production. The grants, he said, supported about 600

jobs and boosted production in December, shoring up funding for

schools and other programs. While he acknowledged that Continental and

other companies were essentially given a multi-million dollar

discount, “that wasn’t the purpose,” he said.

Some environmental advocates have countered that, whatever the intent,

North Dakota effectively gave the oil industry a backdoor subsidy and

sent an implicit signal that taxpayers will come to its rescue when

times are tough.

“In North Dakota I think the story is in some ways a fairly succinct

one,” said Nikki Reisch, director of the climate and energy program at

the Center for International Environmental Law, which highlighted the

state’s program in a recent report. “Taxpayer dollars were being used

to pick up polluters’ tabs, while at the same the state was

repurposing federal funds to support new fracking, making the very

same problem worse.”

’Pollution Vectors’

No one knows how many old wells are scattered across the nation’s oil

and gas fields. According to the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact

Commission, states have identified nearly 57,000 orphaned wells, but

estimate there are hundreds of thousands more undocumented ones. The

EPA has estimated there are more than 3 million abandoned wells,

regardless of whether they have owners or not. Often, companies can

avoid plugging wells when they are no longer productive by calling

them idled, a status that can last decades.

Locally, old wells can contaminate groundwater and foul farmland,

spewing not only petroleum but also toxic, highly salty water.

Abandoned well sites render sections of farmers’ fields unusable.

Companies are generally required to purchase bonds when they drill

wells as a form of insurance—governments can confiscate the bonds if

companies fail to plug their own wells. Lawmakers or regulators

determine the levels for those bonds—for example, $10,000 per well or

$150,000 for all a company’s wells within a state—but in many cases

those levels were set decades ago, and barely begin to cover plugging

costs.

Carbon Tracker has collected data on more than 2.4 million catalogued,

unplugged wells, including all the nation’s active wells, and has

estimated it would cost about $288 billion to plug them. But its

analysis showed that state and federal bonds would cover only about 1

percent of that cost, raising the question of who will pay the

difference if companies go bankrupt or fail to plug their wells. That

estimate for the coverage of bonds excluded Texas, for which Carbon

Tracker was unable to obtain data. Last week, New Mexico’s State Land

Office released a report that found that oil company bonds in the

state covered 2 percent of the expected cleanup costs, falling $8.1

billion short.

Rob Schuwerk, executive director of Carbon Tracker’s North American

office, said the looming transition away from oil and gas will make

the problem worse. It is one thing if industry revenues are stable or

growing, and companies only occasionally bail on their cleanup

responsibilities. But if oil and gas demand begins to decline, the

industry is likely to face falling revenues and a spike in

bankruptcies, just as companies abandon a wave of unprofitable wells.

They might not have money to plug their own wells, leaving taxpayers

on the hook.

An abandoned oil tank from an old oil boom

sits on a ranch in western North Dakota, as a rig drills a new well in

the distance and a flare burns beyond it. Credit: Nicholas Kusnetz

Last year served as a preview, when global lockdowns sent oil demand

plummeting. In North Dakota, that meant oil companies had to shut

their wells and layoff workers as their revenues dwindled.

The conditions prompted warnings of bankruptcies, and led regulators

to ask the state to spend CARES Act relief funds on plugging and

remediating abandoned wells, which they warned could become orphaned

if not addressed.

In order to plug the wells, the state had to assume ownership of them,

a step that was welcomed by Ron Ness, who runs the North Dakota

Petroleum Council, which represents the industry. But at a state

hearing last year, Ness warned regulators against also seizing the

bonds companies had bought as insurance for plugging the wells.

Although the bonds might help pay plugging costs, seizing them would

have “very real” impacts that would prove to be “extremely

problematic,” Ness said.

Ness argued that the CARES Act was effectively reimbursing the state

for the cost of plugging the wells. If regulators did seize the bonds,

he argued, the state could have to return funds to the federal

government.

The petroleum council did not respond to phone messages or emails. But

Schuwerk said that confiscating a bond could pose problems for the

company that purchased it. Bond companies could suddenly view that

company as a risk, and require it to pay higher premiums for its other

bonds, for example, driving up drilling costs.

Regulators have largely granted Ness’s request, at least so far.

According to data provided by the Department of Mineral Resources, the

state confiscated 320 wells and had plugged 280 as of May, at a cost

of $39.3 million, including $6.1 million that came from a state

well-plugging fund financed with industry fees and penalties and taxes

on production. The state “reclaimed”—or cleaned up—only 173 of the

sites.

But so far, the state has confiscated bonds worth only about $3.4

million, while it is pursuing another $1.5 million through civil

action, Helms said. All of that money would go to reimburse the state

fund, rather than the CARES Act money. Helms said that while they are

still looking into it, the rules of the CARES Act may dictate that the

state cannot or should not reimburse the federal government.

The department said that seven companies, responsible for 77 of the

confiscated wells, have either entered bankruptcy or were determined

to be insolvent. The rest of the wells, however, were owned by

companies that continue to pump oil in the state.

Cobra Oil and Gas, for example, had 121 wells confiscated. State

records say the Texas-based company has another 369 active wells,

suggesting there may have been revenue to cover plugging costs. Cobra

did not respond to phone messages or emails.

Keep Environmental Journalism Alive

ICN provides award-winning, localized climate coverage free of charge

and advertising. We rely on donations from readers like you to keep

going to ICN’s donation partner.

Helms said companies like Cobra “are not off the hook,” adding, “I

don’t think I can tell you that we’re going to pursue full

reimbursement, but I think I can commit we’re going to pursue at least

some reimbursement from those companies.”

Helms said the North Dakota Legislature has made changes in bonding

and regulations in recent years that are intended to prevent the

14,000 wells that have been drilled in North Dakota over the past

decade from facing a similar fate. Wells that have been idled for 18

months, for example, are now required to have dedicated bonds, rather

than being covered by a “blanket bond” for all of a company’s wells in

the state.

Wyoming also sent CARES Act funds as grants to oil companies, which

they could use to frack wells they had already drilled or to plug

older wells. According to data provided by the Wyoming Business

Council, which administered the funds, Devon Energy received nearly

$5.8 million, which it used both to frack new wells and plug old ones.

Six other companies, including Occidental Petroleum, received more

than $1 million each.

Randall Luthi, chief energy advisor to Wyoming Gov. Mark Gordon, said

in a statement to Inside Climate News that the spending was

“completely appropriate,” adding that thousands of people in the state

were unable to find work last year. He said the program provided “an

economic and environmental shot in the arm for Wyoming at a time when

it was needed,” and that, “CARES money was always intended for

solvent, but struggling companies.”

Neither Devon, Occidental nor Continental Resources responded to

requests for comment.

Skokos, of the Dakota Resource Council, said he supported cleaning up

old wells, but that the way it was administered was “basically a

bailout for the industry.”

“We could have been using that money for other things like paid family

leave or money for actual workers increasing unemployment,” he said.

“There’s people that were struggling.”

Adam Peltz, a senior attorney with the Environmental Defense Fund,

said it was unlikely that any federal efforts to plug orphaned wells

would be spent on wells with solvent owners, as it was in North Dakota

and Wyoming.

“The overwhelming, vast majority of this money will be spent on

pre-regulatory wells that really have not a trace of an owner on

record,” he said. Pennsylvania, Ohio and other eastern states where

some of the first oil wells were drilled, for example, have hundreds

of thousands of orphaned wells and little funding to plug them. “And

they’re just going to sit there as pollution vectors,” Peltz said,

“until and unless we come up with a lot of money to plug them. The

good news is we’re in a moment where money is flowing for good

causes.”

He noted that some states, including North Dakota, have also begun to

improve their bonding requirements.

But Reisch, of the Center for International Environmental Law, warned

that those changes have hardly begun closing the gap.

“The looming legacy of the oil and gas industry, and of the fossil

fuel economy, is really going to be this ghost infrastructure and

these toxic wells,” she said. “The magnitude of the problem and the

funds needed to address it properly is really daunting.”

Nicholas Kusnetz

Reporter, New York City

Nicholas Kusnetz is a reporter for

InsideClimate News. Before joining ICN, he worked at the Center for

Public Integrity and ProPublica. His work has won numerous awards,

including from the American Association for the Advancement of Science

and the Society of American Business Editors and Writers, and has

appeared in more than a dozen publications, including The Washington

Post, Businessweek, The Nation, Fast Company and The New York Times.

You can reach Nicholas at

nicholas.kusnetz@insideclimatenews.org

and securely at

nicholas.kusnetz@protonmail.com.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

exactrix@exactrix.com

|