|

DARTMOUTH

14

August 2023

By

Dartmouth College

Irrigating more U.S. crops by

mid-century will be worth the investment, researchers say

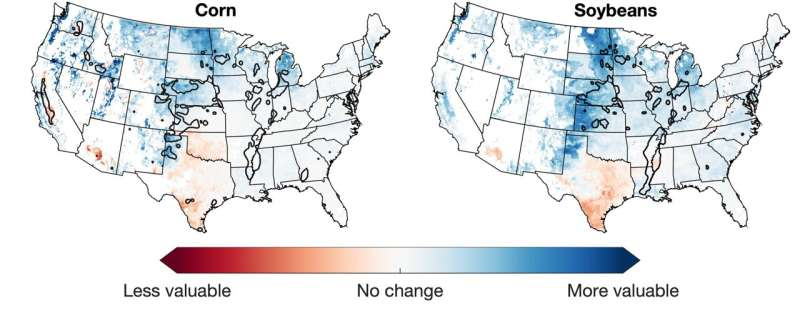

U.S. map of projected change in crop irrigation

value for corn and soybeans by the middle of the 21st century with

currently irrigated areas outlined in black. Credit: Trevor Partridge

et al.

With climate change, irrigating more crops in the United States

will be critical to sustaining future yields, as drought conditions

are likely to increase due to warmer temperatures and shifting

precipitation patterns. Yet less than 20% of croplands are equipped

for irrigation.

A Dartmouth-led study finds that by the middle of the 21st

century under a moderate greenhouse gas emissions scenario, the

benefits of expanded irrigation will outweigh the costs of

installation and operation over an expanded portion of current U.S.

croplands.

The results show that by mid-century corn and soybeans that are

currently rainfed would benefit from irrigation in most of North

Dakota, eastern South Dakota, western Minnesota, Wisconsin, and

Michigan. Soybean farmland that relies on rain throughout parts of

Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, Kansas, and Oklahoma would also

benefit from irrigation. The findings are published in Communications

Earth & Environment.

Installing, maintaining, and running irrigation equipment comes

at a significant cost to farmers, as much as $160 per acre per year.

"Our work essentially creates a U.S. map of where it will make the

most sense to install and use irrigation equipment for corn and

soybean crops in the future," says first author Trevor Partridge, a

Mendenhall Postdoctoral Fellow and research hydrologist with the U.S.

Geological Survey Water Resources Mission Area, who conducted the

study while working on his Ph.D. at Dartmouth.

The High Plains region, including Nebraska, Kansas, and

northern Texas, has historically been one of the most heavily

irrigated areas, and was found to have the highest current economic

returns for irrigation. However, the increasing costs of drought are

pushing farmers to invest in irrigation throughout regions of the Corn

Belt and southeastern U.S., and the long-term economic return on these

investments is difficult to predict.

To conduct the cost-benefit analysis of irrigating corn and

soybeans, the researchers ran a series of crop model simulations. They

applied several global climate projections that span the range of

potential future climates—hot and dry, hot and wet, cool and dry, cool

and wet, each relative to the average climate projection—to simulate

future crop growth under fully irrigated or rain-fed conditions.

For each climate scenario, the crop model was run for both corn

and soybeans across all cultivated areas in the U.S. The crop model

simulations examined three periods: historical (1981–2010),

mid-century (2036–2065), and end-of-century (2071–2100) under moderate

and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. The simulations factored

in county-level crop management and growth data from the U.S.

Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistical Service,

including planting, maturity, and harvest dates.

To determine the economic benefits of irrigating—the team

calculated the additional simulated crop yield from irrigating and the

corresponding increased market value that could be expected—relative

to the irrigation costs, which included the electricity required to

pump groundwater and distribute it over the field, and associated

expenses per acre to own and operate the irrigation system.

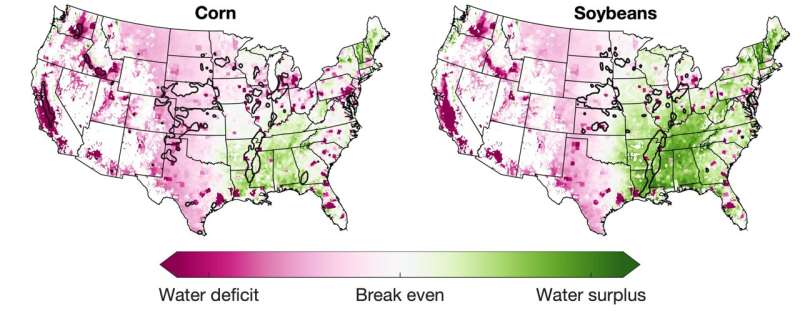

The team investigated not only where and when it makes sense to

install irrigation for corn and soybeans but also if there will be

enough water to do so. They calculated the "irrigation water deficit,"

which is the simple difference between how much water is applied to

the field relative to how much water should be available for

irrigation.

U.S. map of projected change in crop irrigation

value for corn and soybeans by the middle of the 21st century with

currently irrigated areas outlined in black. Credit: Trevor Partridge

et al.

With climate change, irrigating more crops in the United States

will be critical to sustaining future yields, as drought conditions

are likely to increase due to warmer temperatures and shifting

precipitation patterns. Yet less than 20% of croplands are equipped

for irrigation.

A Dartmouth-led study finds that by the middle of the 21st

century under a moderate greenhouse gas emissions scenario, the

benefits of expanded irrigation will outweigh the costs of

installation and operation over an expanded portion of current U.S.

croplands.

The results show that by mid-century corn and soybeans that are

currently rainfed would benefit from irrigation in most of North

Dakota, eastern South Dakota, western Minnesota, Wisconsin, and

Michigan. Soybean farmland that relies on rain throughout parts of

Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, Kentucky, Kansas, and Oklahoma would also

benefit from irrigation. The findings are published in Communications

Earth & Environment.

Installing, maintaining, and running irrigation equipment comes

at a significant cost to farmers, as much as $160 per acre per year.

"Our work essentially creates a U.S. map of where it will make the

most sense to install and use irrigation equipment for corn and

soybean crops in the future," says first author Trevor Partridge, a

Mendenhall Postdoctoral Fellow and research hydrologist with the U.S.

Geological Survey Water Resources Mission Area, who conducted the

study while working on his Ph.D. at Dartmouth.

The High Plains region, including Nebraska, Kansas, and

northern Texas, has historically been one of the most heavily

irrigated areas, and was found to have the highest current economic

returns for irrigation. However, the increasing costs of drought are

pushing farmers to invest in irrigation throughout regions of the Corn

Belt and southeastern U.S., and the long-term economic return on these

investments is difficult to predict.

To conduct the cost-benefit analysis of irrigating corn and

soybeans, the researchers ran a series of crop model simulations. They

applied several global climate projections that span the range of

potential future climates—hot and dry, hot and wet, cool and dry, cool

and wet, each relative to the average climate projection—to simulate

future crop growth under fully irrigated or rain-fed conditions.

For each climate scenario, the crop model was run for both corn

and soybeans across all cultivated areas in the U.S. The crop model

simulations examined three periods: historical (1981–2010),

mid-century (2036–2065), and end-of-century (2071–2100) under moderate

and high greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. The simulations factored

in county-level crop management and growth data from the U.S.

Department of Agriculture National Agricultural Statistical Service,

including planting, maturity, and harvest dates.

To determine the economic benefits of irrigating—the team

calculated the additional simulated crop yield from irrigating and the

corresponding increased market value that could be expected—relative

to the irrigation costs, which included the electricity required to

pump groundwater and distribute it over the field, and associated

expenses per acre to own and operate the irrigation system.

The team investigated not only where and when it makes sense to

install irrigation for corn and soybeans but also if there will be

enough water to do so. They calculated the "irrigation water deficit,"

which is the simple difference between how much water is applied to

the field relative to how much water should be available for

irrigation.

U.S. map of projected mid-century irrigation

groundwater deficit—the volumetric difference between irrigated water

and available water—with currently irrigated corn and soybean areas

outlined in black. Credit: Trevor Partridge et al.

The results show that by mid-century there will likely be

enough water to irrigate soybeans in Iowa, Wisconsin, Ohio, and

northern Illinois and Indiana, but not corn. Iowa is the largest

producer of corn in the U.S. groundwater resources for irrigation were

found to be the most abundant in the southeast U.S., especially in the

lower Mississippi Valley where agriculture is less intensive. However,

in this region the benefits of irrigation are minimal.

"Our results suggest that there is relatively little overlap

between where there is enough water to fully irrigate crops without

placing additional stress on water resources and where farmers can

expect the investment in irrigation to pay for itself over the long

term, " says Partridge.

For example, the Ogallala Aquifer in the Great Plains is the

largest aquifer in the U.S., providing water to eight states, and

supports one the most extensively irrigated areas for corn and

soybeans.

"The increasing benefits of irrigation, could incentivize

farmers to use more water, which will place additional stress on key

aquifers, including the Ogallala," says senior author Jonathan Winter,

an associate professor of geography and lead of the Applied

Hydroclimatology Group at Dartmouth. Prior research has shown that

water is being extracted from the Ogallala Aquifer faster than it can

be replenished. "There's just not enough water to continue irrigating

at the current rate from the Ogallala, especially in the southern

portion where groundwater levels are rapidly falling," says Winter.

With greater warming, such as end-of-century under a high

greenhouse gas emissions scenario, heat stress will dominate impacts

on crop yields and reduce the effectiveness of irrigation as an

adaptation strategy throughout most of the U.S., especially for corn.

Corn typically has a higher yield than soybean, but soybeans are more

heat tolerant, don't require as much water, and have a slightly

shorter growing season.

"By the end of the century, our simulations suggest that it

will be more economically beneficial to irrigate soybeans than corn,"

says Winter. "Once irrigation is installed, we could see some places

that historically grew corn switch to soybeans because it's a low-cost

adaptation."

When it comes to irrigation, farmers must consider a range of

complex and competing factors: previous yield performance, crop market

values, energy costs, economic incentives, and seasonal weather

forecasts. The researchers hope that their analysis can be used to

help agricultural and water resource management policies in adapting

to a warmer climate.

More information: Irrigation

benefits outweigh costs in more US croplands by mid-century, Communications

Earth & Environment (2023). DOI:

10.1038/s43247-023-00889-0 , www.nature.com/articles/s43247-023-00889-0

Journal information: Communications

Earth & Environment

Provided by Dartmouth

College

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

509 995 1879

Cell, Pacific Time Zone.

General office:

509-254

6854

4501 East Trent

Ave.

Spokane, WA 99212

|