Is it cheaper to refuel your EV

battery or gas tank? We did the math in all 50 states.

Gasoline cars are cheaper to refuel than

electric vehicles.

I’ve heard this claim pop up everywhere from Massachusetts to Fox News

over the past two years. My neighbor even refuses to plug in his

hybrid Toyota RAV4 Prime over what he calls ruinous electricity rates.

What gives?

The basic argument is that electricity prices are so high it has

erased the advantage of recharging over refilling. This cuts to the

heart of why many people buy EVs, according to the Pew Research

Center: 70 percent of potential EV buyers report “saving money on gas”

as among their top reasons.

So how much does it really cost to refuel an EV?

The answer is less straightforward than it seems. Just calculating the

cost of gasoline vs. electricity is misleading. Prices vary by charger

(and state). Everyone charges differently. Road taxes, rebates and

battery efficiency all affect the final calculation.

So I asked researchers at the nonpartisan Energy Innovation, a policy

think tank aimed at decarbonizing the energy sector, to help me nail

down the true cost of refueling in all 50 states by drawing on data

sets from federal agencies, AAA and others. You can dive into their

helpful tool here.

I used the data to embark on two hypothetical road trips across

America, delivering a verdict on whether it costs more to refill or

recharge during the summer of 2023.

The results surprised me (and they might really surprise my neighbor).

The cost of a fill-up

If you’re like 4 in 10 Americans, you’re considering buying an

electric vehicle. And if you’re like me, you’re sweating the cost.

The average EV sells for $4,600 more than the median gasoline car, but

by most calculations, I’ll save money over the long run. It costs less

to refuel and maintain the vehicle — hundreds of dollars less per

year, by some estimates. That’s before government incentives, and any

consideration of never visiting a gas station again.

Yet nailing down a precise number is tricky. The average price of a

gallon of gasoline is easy to calculate. Since 2010, the price, in

inflation-adjusted terms, is virtually unchanged, according to data

from the Federal Reserve.

The same applies to a kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity. But the cost

of recharging, by contrast, is far more opaque.

Electricity rates not only vary by state, but by the time of day and

even the outlet. EV owners may plug in at home or work and then pay a

premium to fast-charge on the road.

That makes comparing the cost of a “fill-up” for a gasoline Ford

F-150, America’s best-selling vehicle since the 1980s, and its

electric counterpart’s 98-kWh battery challenging. It requires

assumptions about geography, charging behavior and standardizing how

the energy in batteries and gas tanks convert into miles. Such

calculations must then be applied to different vehicle classes, such

as sedans, SUVs and trucks.

No wonder almost no one does it. But we saved you the time. The

results reveal just how much you can save — and the few instances

where you won’t.

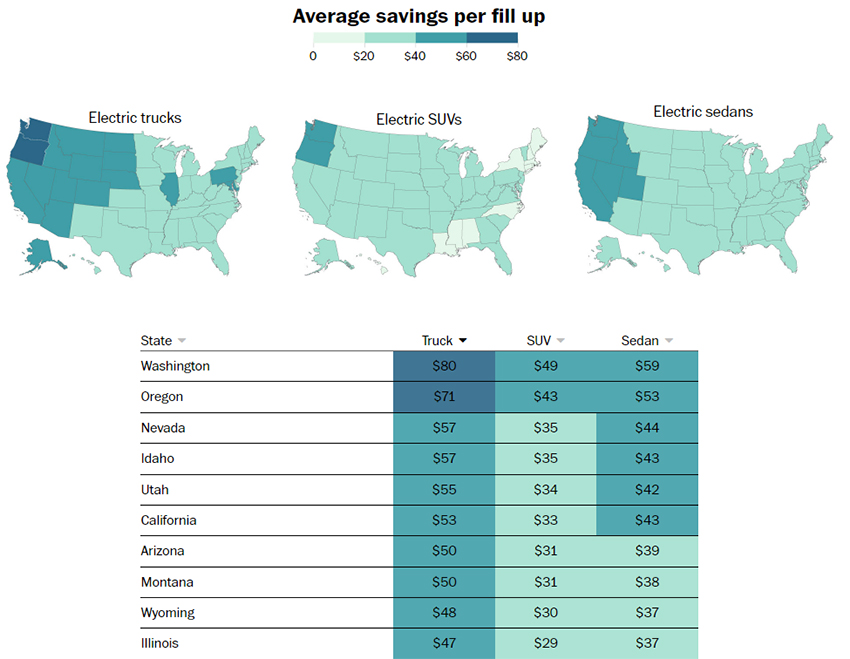

The bottom line? In all 50 states, it’s cheaper for the everyday

American to fill up with electrons — and much cheaper in some regions

such as the Pacific Northwest, with low electricity rates and high gas

prices.

In Washington state, with prices around $4.98 per

gallon of gas, it costs about $115 to fill up an F-150 which delivers

483 miles of range.

By contrast, recharging the electric F-150 Lightning (or Rivian R1T)

to cover an equivalent distance costs about $34 — an $80 savings. This

assumes, as the Energy Department estimates, drivers recharge at home

80 percent of the time, along with other methodological assumptions at

the end of this article.

But what about the other extreme? In the Southeast, which has low gas

prices and electricity rates, savings are lower but still significant.

In Mississippi, for example, a conventional pickup costs about $30

more to refuel than its electric counterpart. For smaller, more

efficient SUVs and sedans, EVs save roughly $20 to $25 per fill-up to

cover the same number of miles.

An American driving the average 14,000 miles per

year would see annual savings of roughly $700 for an electric SUV or

sedan up to $1,000 for a pickup, according to Energy Innovation.

But daily driving is one thing. To put the model to the test, I took

these estimates on two all-American summer road trips.

Tale of two road trips

You’ll encounter two main kinds of chargers on the open road. Level 2

chargers add about 30 miles of range every hour. Prices range from

about 20 cents per kWh to free at many businesses such as hotels and

grocery stores hoping to attract customers (Energy Innovation assumes

just over 10 cents per kWh in the estimates below).

Fast chargers known as Level 3 — nearly 20 times faster — can top off

an EV battery to about 80 percent in as little as 20 minutes. But that

typically costs 30 to 48 cents per kWh — a price equivalent to

gasoline in some places, as I later found out.

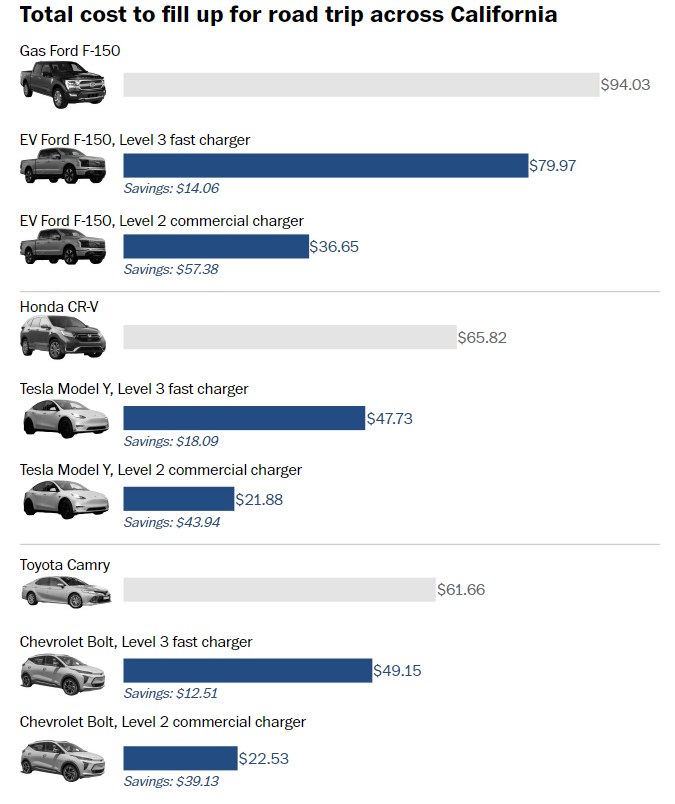

To test how this plays out, I embarked on a hypothetical 408-mile road

trip from San Francisco to Disneyland, just south of Los Angeles. For

the journey, I selected the F-150 and its electric counterpart, the

Lightning, part of the wildly popular series that sold 653,957 units

last year. There’s a strong climate case against building electric

versions of America’s gas guzzlers, but these estimates are meant to

reflect the actual vehicle preferences of Americans.

The winner? The EV — barely. The savings were

modest because of the substantial premium for using fast chargers,

typically three to four times more expensive than charging at home. In

a Lightning, I arrived at the park with $14 more in my pocket than if

I had driven its gasoline counterpart.

If I decided to make a longer stop at Level 2 chargers at hotels or

restaurants, my savings would have been $57. This trend held for

smaller vehicles, too: Tesla’s Model Y crossover saved me $18 and $44

for the 408-mile journey at Level 3 and Level 2 chargers,

respectively, compared to refueling with gasoline.

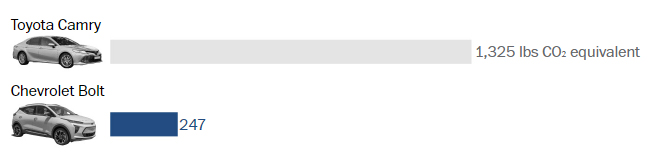

On the emissions front, EVs pulled well ahead.

EVs emit less than a third of the emissions per mile than their

gasoline counterparts — and they’re getting cleaner every year.

America’s electricity mix emits just under a pound of carbon emissions

for every kWh generated, according to the Energy Information

Administration. By 2035, the White House hopes to drive that closer to

zero. This meant the conventional F-150 spewed five times more

greenhouse gas emissions into the atmosphere than the Lightning. The

Tesla Model Y represented 63 pounds of greenhouse gas emissions on the

trip compared to more than 300 pounds from all the conventional

vehicles.

Driving where few EVs go

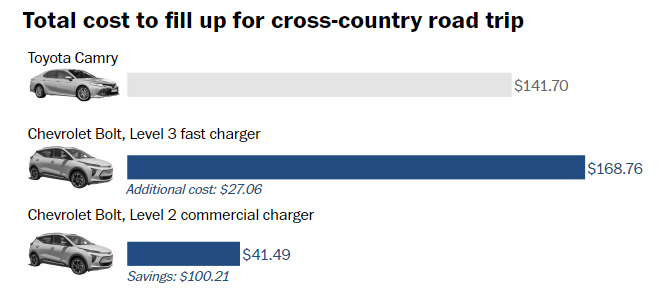

The true test, however, would be a journey from Detroit to Miami.

Driving from Motown across the Midwest is not an EV dream. This region

has some of the lowest EV ownership rates in the United States.

Chargers are not as plentiful. Gasoline prices are low. Electricity is

dirtier.

To make it even more lopsided, I chose to compare the Toyota Camry

with the electric Chevrolet Bolt — relatively efficient vehicles that

narrow the difference in fueling costs. To reflect each state’s mix of

prices, I measured the distance along the 1,401-mile journey in all

six states, and their respective energy costs and emissions.

Did the EV hold its edge? Sometimes. But not

always.

If I was refueling at homes or cheap Level 2 commercial stations along

the way (an unlikely scenario), the Bolt EV was cheaper to refuel: $41

compared to $142 for the Camry.

But fast charging tipped the balance in favor of the Camry. At Level 3

chargers, the retail cost of electricity added up to $169 to complete

the trip on batteries, $27 more than the gasoline-powered journey.

On greenhouse gas emissions, however, the Bolt

was the clear leader, indirectly accounting for just 20 percent of the

emissions coming from its counterpart.

Total emissions for cross-country road trip

Do EV detractors have a point?

I wanted to see why those arguing against the economics of EVs came to

such a different conclusion. For this, I contacted Patrick Anderson,

whose Michigan-based consulting firm works with the auto industry and

assesses the cost of EVs each year. It has consistently found most EVs

to be more expensive to refuel.

Anderson told me that many economists leave out costs that should be

part of any calculation of recharging costs: state

EV taxes replacing gas taxes, costs of home chargers, transmission

losses while recharging (about

10 percent), and the cost of driving to sometimes distant public

fueling stations. These are small but real costs, he says. Together,

they tip the balance toward gasoline cars.

Mid-priced gasoline vehicles, by

his calculations, cost less to refuel — approximately $11 to drive

100 miles compared to $13 to $16 for comparable EVs. The exceptions

were luxury vehicles since they tend to be less efficient and burn

premium fuel. “This segment is where EVs makes a lot of sense for the

median buyer,” says Anderson. “It’s not surprising that’s where we’re

seeing the most sales.”

But critics

say Anderson’s assessment overestimates or omits key assumptions:

his firm’s

analysis assumes EV owners use expensive public stations about 40

percent of the time (the Energy

Department estimates about 20 percent), overstates battery

efficiency losses, adds the “cost” of free public chargers in the form

of “property taxes, tuition, consumer prices or investor burdens” and

ignores government and manufacturing incentives.

The true cost of a fill-up

Ultimately, we may never agree on what it costs to refuel an electric

vehicle. That may not matter. For the everyday driver in the United

States, it’s already cheaper to refuel an EV most of the time, and

it’s expected to

get cheaper as renewable capacity expands and vehicle efficiency

improves.

The sticker price for some EVs is expected to fall

below comparable gasoline cars as soon as this year, and estimates

of the total cost of ownership — maintenance, fuel and other costs

over a vehicle’s lifetime — suggest EVs are already cheaper.

After that there’s one last number I felt was missing: the social

cost of carbon. It’s a rough dollar estimate of the damage from

adding another ton of carbon to the atmosphere — a tally of heat

deaths, flooding, wildfires, crop failures and other costs tied to

global warming.

Every gallon of gas adds about 20

pounds of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, equivalent to about 50

cents in climate damage per gallon, researchers estimate.

Accounting for external factors such as congestion, accidents and air

pollution, according to one 2007 estimate by Resources for the Future,

the damage bill is closer to $3

per gallon.

You’re not required to pay this, of course. And EVs also don’t solve

this problem on their own. For that, we’ll need more cities and

neighborhoods where you don’t need a car to visit

friends or buy groceries.

But electric mobility is essential

to helping keep temperature increases below 2 degrees Celsius. The

alternative is a price that has become impossible to ignore.

About this story

The costs to fill up an EV vs. a gasoline vehicle were

calculated for three vehicle classes: sedans, SUVs and trucks.

All vehicle selections are 2023 base models. The average miles

traveled by a driver per year was assumed to be 14,263,

based on 2019 Federal Highway Administration data. For all

vehicles, assumptions for range, mileage and emissions were

drawn from the Environmental Protection Agency’s fueleconomy.gov.

Gas prices are based on July

2023 data from AAA. For EVs, the average number of

kilowatt-hours required for a full charge was calculated based

on the battery size. Charging location was based on Energy

Department research indicating that 80

percent of charging is at home. Residential electricity

rates were provided by the Energy Information Administration

from 2022. The remaining 20 percent of charging was at public

charging stations, with electricity rates based on Electrify

America’s published rates by state.

These calculations do not incorporate any assumptions for total

cost of ownership, EV tax credits, registration fees, or

operation and maintenance expenses. We also do not assume any EV-related

rate designs, EV charging discounts or free charging, or

electric time-of-use pricing.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

Nathan1@greenplayammonia.com

exactrix@exactrix.com