|

Carbon

removal's hard problems

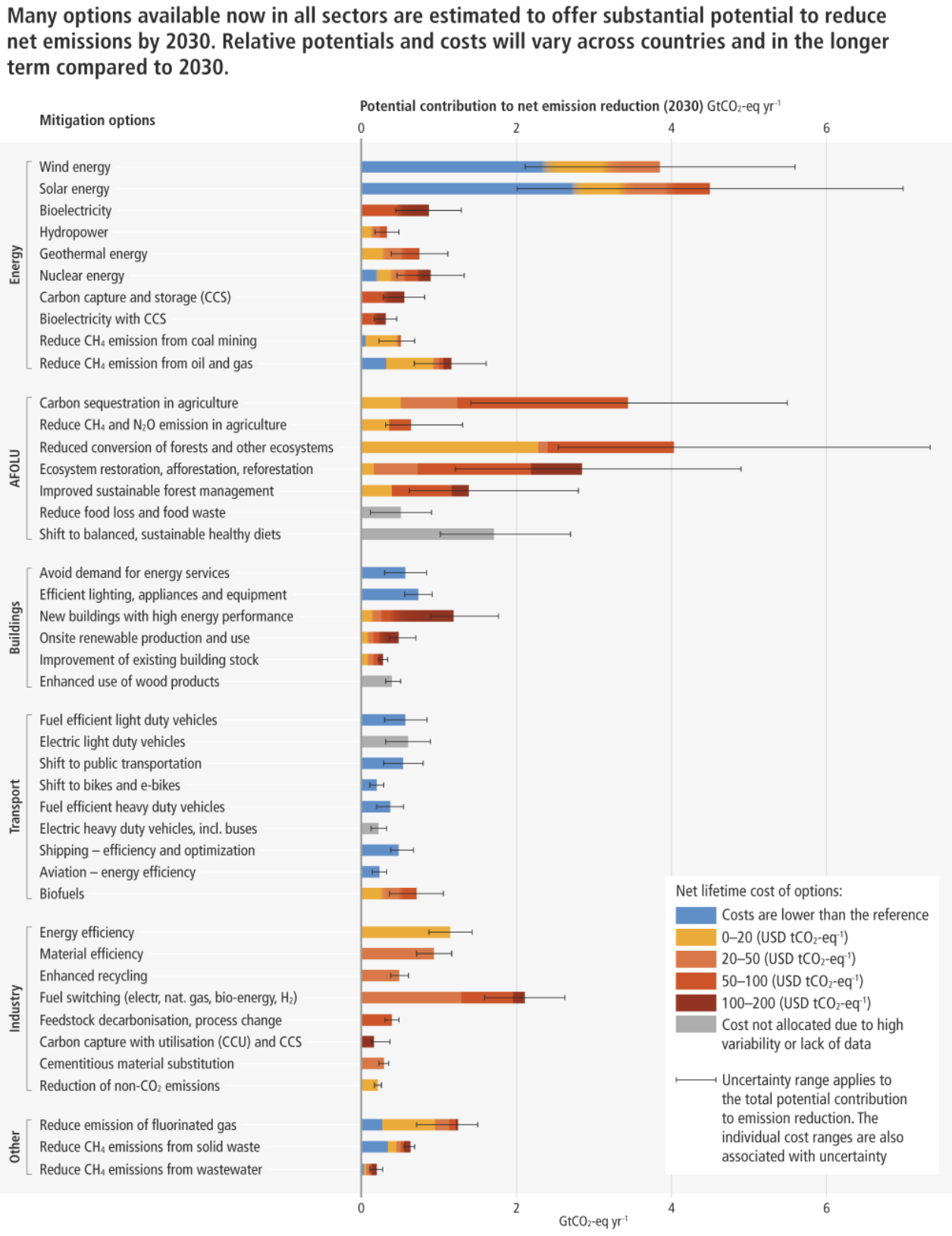

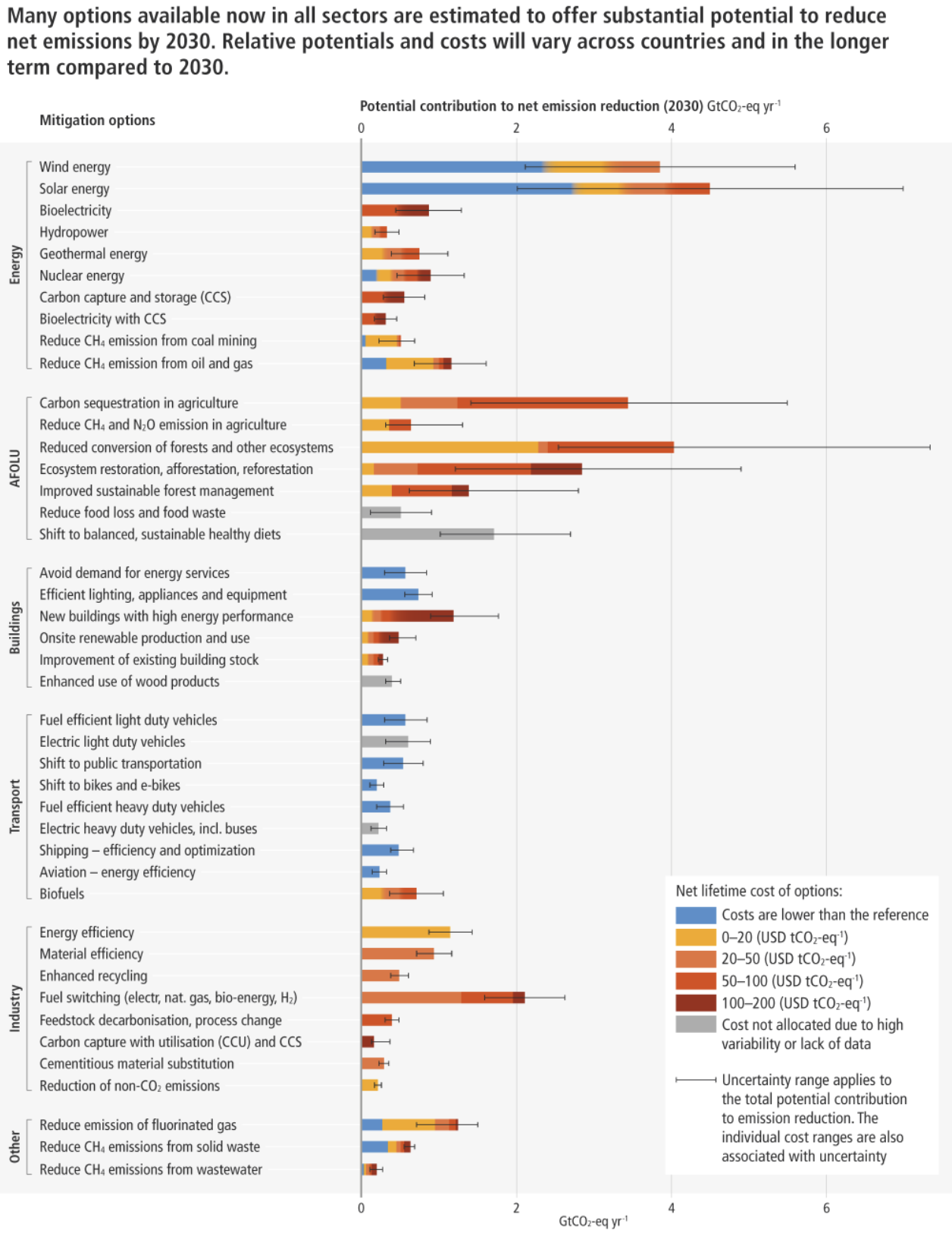

The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s

latest report sent

a stark alert about the world’s current emissions and temperature

trajectory. Within the document is a complex chart that

maps out dozens of technologies or practices which can reduce

emissions, their potential to do so this decade, and the economics of

deploying them.

Source:

IPCC Source: IPCC

The charts are color-coded. Anything blue is cost-competitive today;

anything in the range from light orange to dark red indicates a need

for investment beyond business as usual. Wind and solar energy are

winners in terms of cost and scale, with gigatons of potential

emissions reduction per year. So too are a half-dozen transportation

approaches. Industrial measures have significant potential, but carry

a high cost. Building applications, in particular energy services and

lighting, are in the money but others such as the rather broad

“improvement of existing building stock” are not.

At the bottom of the energy section is a small (in terms of 2030

potential) and angry (in its bright red colors) bar for carbon capture

and storage. It has limited emissions potential within this decade,

and it is expensive.

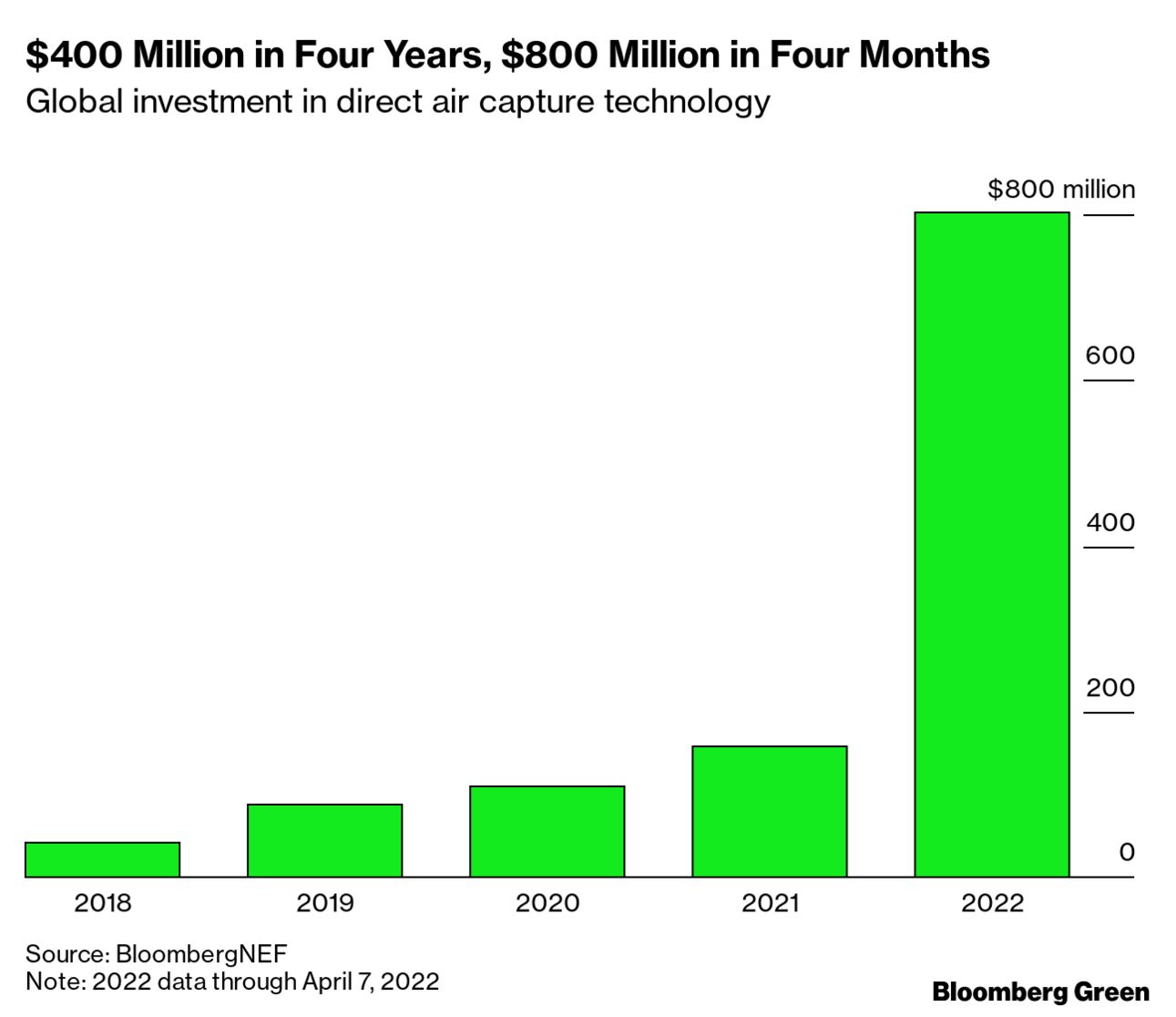

Just as the IPCC’s report dropped, Swiss carbon removal company

Climeworks AG announced it

had raised $650 million. This investment is by far the

largest in any carbon removal company. There is now twice as much

investment in this particular carbon capture technology in the first

four months of 2022 as in the prior four years.

Just as important as the amount of the investment is the size of main

investors. Partners Group AG manages $127 billion; Baillie Gifford,

more than $450 billion as of December 2021; GIC, Singapore’s sovereign

fund, an estimated $700 billion-plus — all told, well over $1 trillion

dollars under management. The commitment to carbon removal more

broadly is significant.

The vice-chair of the working group which produced this latest IPCC

report has said that carbon removal is “essential” to zero

out greenhouse gas emissions. But being essential to long-term climate

goals does not inherently make a market. A list of investors like the

group above does imply there will be a market for carbon removal at

scale, even in the absence of any major global policy support.

Also, carbon removal

not only has a cost of operation, it is a

cost, as Shayle Kann of Energy Impact Partners says. Carbon removal

requires capital to build plants and it requires substantial energy to

power the removal processes. More than that, though, it provides a

societal good but does not provide electrons, or molecules, or

services in the way that renewable power or building energy services

do.

Capturing carbon dioxide molecules at massive scale, and storing them

stably for centuries or longer, is a hard problem to solve. The

companies doing carbon removal are what their investors often call

“hard tech” — their work is complex and requires time-consuming

hardware and infrastructure (not software and services). Success will

not be quick, and in fact may not come until after the 2030 interval

of the IPCC’s report.

In 1976 Amory Lovins, the cofounder and chairman emeritus of energy

think tank RMI, wrote a short but significant essay about U.S.

energy’s future. In it, he contrasted the current — and expected

— system of massive power plants and complex engineering as the “hard

path” to the future. The alternative is a “soft path” that relies on

“smaller, far simpler supply systems entailing vastly shorter

development and construction time, and on smaller, less sophisticated

management systems.”

More than four decades later the IPCC is clear that while the soft

path is scaling rapidly, the hard path still will be needed to solve

hard problems. Technology developers and investors seem to think so

too.

Nathaniel Bullard is BloombergNEF's Chief Content Officer.

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

exactrix@exactrix.com

|