|

July

20, 2023

BY BRITTANY

PETERSON AND SIBI

ARASU

Solar panels on water canals seem

like a no-brainer. So why aren’t they widespread?

DENVER (AP) — Back in 2015, California’s dry

earth was crunching under a fourth year of drought. Then-Governor

Jerry Brown ordered an unprecedented 25% reduction in home water use.

Farmers, who use the most water, volunteered too to avoid deeper,

mandatory cuts.

Brown also set a goal for the state to get half its energy from

renewable sources, with climate change bearing down.

Yet when Jordan Harris and Robin Raj went knocking on doors with an

idea that addresses both water loss and climate pollution — installing

solar panels over irrigation canals — they couldn’t get anyone to

commit.

Fast forward eight years. With devastating heat,

record-breaking wildfire, looming crisis on the Colorado River, a

growing commitment to fighting climate change, and a little bit of

movement-building, their company Solar AquaGrid is preparing to break

ground on the first solar-covered canal project in the United States.

“All of these coming together at this moment,” Harris said. “Is there

a more pressing issue that we could apply our time to?”

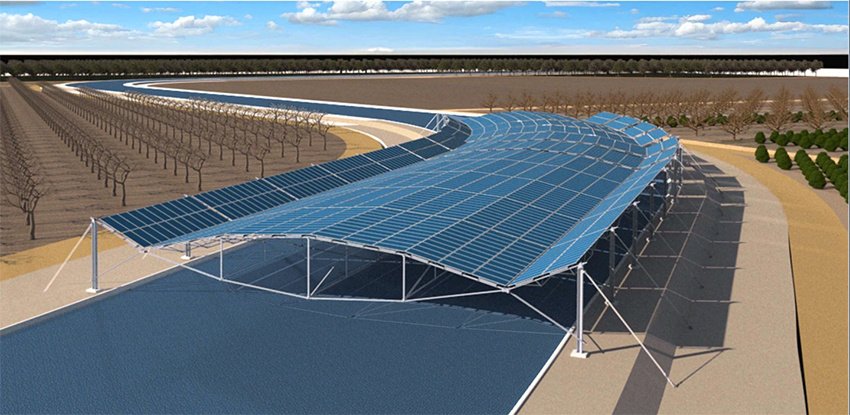

The idea is simple: install solar panels over canals in sunny,

water-scarce regions where they reduce evaporation and make

electricity.

A study by the University of California, Merced gives a boost to the

idea, estimating that 63 billion gallons of water could be saved by

covering California’s 4,000 miles of canals with solar panels that

could also generate 13 gigawatts of power. That’s enough for the

entire city of Los Angeles from January through early October.

But that’s an estimate — neither it, nor other potential benefits have

been tested scientifically. That’s about to change with Project Nexus

in California’s Central Valley.

Indian workers give finishing touches to

installed solar panels covering the Narmada canal at Chandrasan

village, outside Ahmadabad, India, April 22, 2012. (AP Photo/Ajit

Solanki, File)

BUILDING MOMENTUM

Solar on canals has long been discussed as a two-for-one solution

in California, where affordable land for energy development is as

scarce as water. But the grand idea was still a hypothetical.

Harris, a former record label executive, co-founded “Rock the Vote,”

the voter registration push in the early 1990s, and Raj organized

socially responsible and sustainability campaigns for businesses. They

knew that people needed a nudge - ideally one from a trusted source.

They thought research from a reputable institution might do the trick,

and got funding for UC Merced to study the impact of

solar-covered-canals in California.

The study’s results have taken off.

They reached Governor Gavin Newsom, who called Wade Crowfoot, his

secretary of natural resources.

“Let’s get this in the ground and see what’s possible,” Crowfoot

recalled the governor saying.

Indian laborers work amid installed solar panels atop the Narmada

canal at Chandrasan village, outside Ahmadabad, India, Feb. 16, 2012.

(AP Photo/Ajit Solanki, File)

Around

the same time, the Turlock Irrigation District, an entity that also

provides power, reached out to UC Merced. It was looking to build a

solar project to comply with the state’s increased goal of 100%

renewable energy by 2045. But land was very expensive, so building

atop existing infrastructure was appealing. Then there was the

prospect that shade from panels might reduce weeds growing in the

canals — a problem that costs this utility $1 million annually.

“Until this UC Merced paper came out, we never really saw what those

co-benefits would be,” said Josh Weimer, external affairs manager for

the district. “If somebody was going to pilot this concept, we wanted

to make sure it was us.”

The state committed $20 million in public funds, turning the pilot

into a three-party collaboration among the private, public and

academic sectors. About 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) of canals between

20 and 110 feet wide will be covered with solar panels between five

and 15 feet off the ground.

The UC Merced team will study impacts ranging from evaporation to

water quality, said Brandi McKuin, lead researcher on the study.

“We need to get to the heart of those questions before we make any

recommendations about how to do this more widely,” she said.

LESSONS LEARNED ABROAD

California isn’t first with this technology. India pioneered it on one

of the largest irrigation projects in the world. The Sardar Sarovar

dam and canal project brings water to hundreds of thousands of

villages in the dry, arid regions of western India’s Gujarat state.

Then-chief minister of Gujarat state, Narendra Modi, now the country’s

prime minister, inaugurated it in 2012 with much fanfare. Sun Edison,

the engineering firm, promised 19,000 km (11,800 miles) of solar

canals. But only a handful of smaller projects have gone up since. The

firm filed for bankruptcy.

“The capital costs are really high, and maintenance is an issue,” said

Jaydip Parmar an engineer in Gujarat who oversees several small solar

canal projects.

A worker washes his hands as installed solar panels are visible atop

the Narmada canal at Chandrasan village, outside of Ahmadabad, India,

Feb. 16, 2012. (AP Photo/Ajit Solanki)

With

ample arid land, ground-based solar makes more sense there

economically, he said.

Clunky design is another reason the technology hasn’t been widely

adopted in India. The panels in Gujarat’s pilot project sit directly

over the canal, limiting access for maintenance and emergency crews.

Back in California, Harris took note of India’s experience, and began

a search for a better solution. The project there will use better

materials and sit higher.

NEXT STEPS

Project Nexus may not be alone for long. The Gila River Indian Tribe

received funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to install

solar on their canals in an effort to save water to ease stress on the

Colorado River. And one of Arizona’s largest water and power

utilities, the Salt River Project, is studying the technology

alongside Arizona State University.

Still, rapid change isn’t exactly embraced in the world of water

infrastructure, said Representative Jared Huffman, D-Calif.

“It’s an ossified bastion of stodgy old engineers,” he said.

Huffman has been talking up the technology for almost a decade, and

said he finds folks are still far more interested in building taller

dams than what he says is a much more sensible idea.

He pushed a $25 million provision through last year’s Inflation

Reduction Act to fund a pilot project for the Bureau of Reclamation.

Project sites for that one are currently being evaluated.

And a group of more than 100 climate advocacy groups, including the

Center for Biological Diversity and Greenpeace, have now sent a letter

to Interior Secretary Deb Haaland and Bureau Commissioner Camille

Touton urging them “to accelerate the widespread deployment of solar

photovoltaic energy systems” above the Bureau’s canals and aqueducts.

Covering all 8,000 miles of Bureau-owned canals and aqueducts could

“generate over 25 gigawatts of renewable energy — enough to power

nearly 20 million homes — and reduce water evaporation by tens of

billions of gallons.”

Covering every canal would be ideal, Huffman said, but starting with

the California Aqueduct and the Delta Mendota canal, “it’s a really

compelling case,” he said. “And it’s about time that we started doing

this.”

___

Arasu reported from Bengaluru, India.

___ The Associated Press receives support from the Walton Family

Foundation for coverage of water and environmental policy. The AP is

solely responsible for all content. For all of AP’s environmental

coverage, visit https://apnews.com/hub/climate-and-environment

Green Play Ammonia™, Yielder® NFuel Energy.

Spokane, Washington. 99212

www.exactrix.com

509 995 1879 cell, Pacific.

Nathan1@greenplayammonia.com

exactrix@exactrix.com

|